-

Dry Branch

To understand the past, we must understand places. — Lewis R. Binford

The late archaeologist Lewis Binford (1931–2011) pioneered the application of ethnographic observation to the construction of archaeological theory, particularly as it applied to that long span of time during which the pre-agricultural or hunting-and-gathering adaptation was exclusively operative. In a series of highly influential writings published in the early 1980s (e.g., Binford 1980, 1982, 1983) he provided perspectives on the relationship between the distribution of complex living systems and their material correlates in space that challenged what he referred to as the traditional “normative view” of Old and New World cultural historians. Binford suggested that patterns registered in the archaeological record, particularly those at deep stratified sites with very long sequences, could not be reliably “read” without a more complete understanding of the effects of mobility and long-term land use patterns on the changing use of the same places in a landscape. Later in time, with increasing population density and reduced mobility,

We may anticipate increasing repetition in the use of particular places . . . It should be clear that when residential mobility is at a minimum the economic potential of fixed places in the surrounding habitat will remain basically the same, other things being equal. This means that a system changing in the direction of increased sedentism should generate ancillary sites with increasing content homogeneity. This should have the cumulative effect of yielding a regional archaeological record characterized by greater intersite diversity among ancillary or non-residentially used sites but less intrasite diversity arising in the context of multiple occupations (Binford 1982:20).

From the more mundane perspective of the field archaeologist, Binford is pointing out that we have much to learn from small artifact accumulations generated during short duration use or occupation of a place. The durable material remains recovered from demonstrably short-duration sites are referred to as assemblages. One such assemblage, recovered from the West Tennessee Coastal Plain, is described here, and situated within our developing picture of the larger regional occupation of the land along the Hatchie River around AD 1200.

The Dry Branch site (40HM159) is situated on a long, elevated finger ridge of eroded silty clay loam between 460-465 feet above mean sea level (Figure 1). It is near the northern terminus of a substantial interfluvial upland separating Spring Creek and the main channel of the Hatchie River. An ancient major north-south Indian trail passed along this landform, crossing the Hatchie near present-day Bolivar, and continued to the northeast into the upper section of the Forked Deer and beyond (Figure 4; Ball 2014; Myer 1928). Another major trail ran from here to the Mississippi River west of the site. The nearest water is 220 m south-southeast, but the site is near the head of a small stream and permanent water may have been located at a greater distance from the site during early fall when precipitation is minimal. The site locale provides an excellent view of the lower lying narrow floodplain to the east.

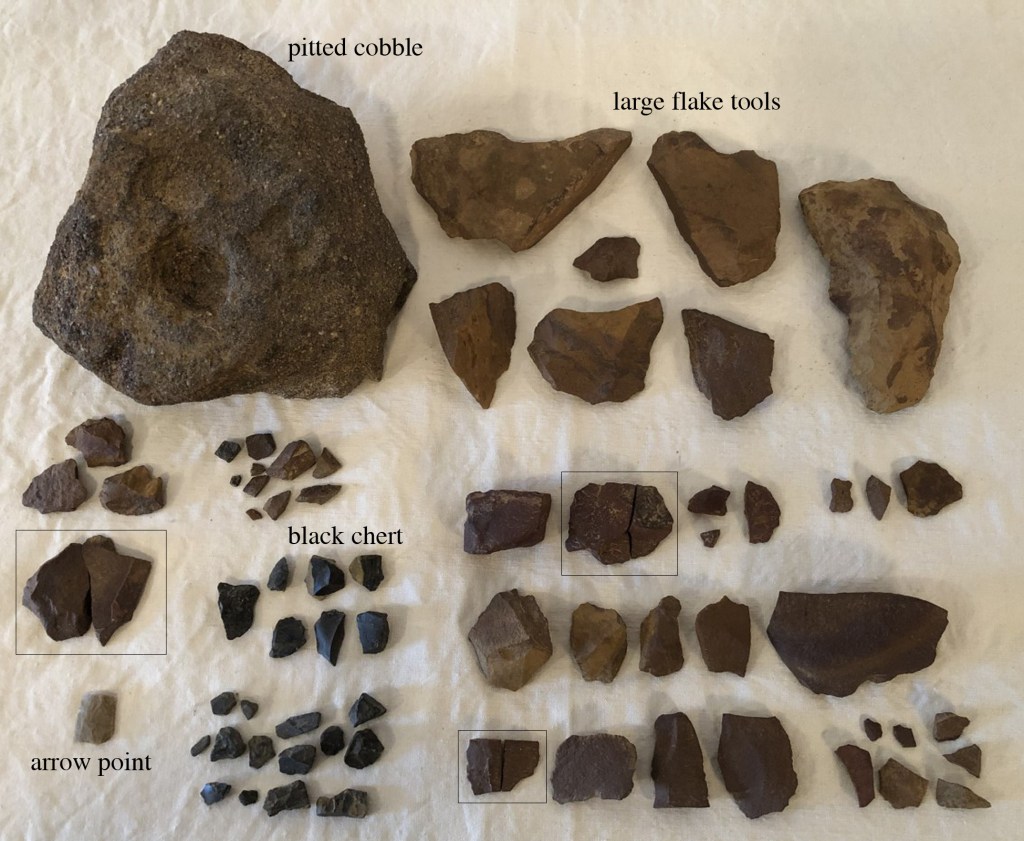

Figure 1. Distribution of artifacts and soil on the ridge at Dry Branch. The Dry Branch site was initially identified in the fall of 2010 while walking fields adjacent to the parcel to the immediate north. Prehistoric artifacts were observed on the surface and periphery of an exposed field road in the vicinity of a stunted Catawba tree in an area covering no more than about 600 square meters. The farm road passing along the ridge post-dates 1950. This landform was wooded on the 1950 USGS quadrangle sheet and the subsequent photo-revision shows clearing of the ridge by 1983. The artifacts are restricted to the site surface and there is no indication of organic deposits. The surface material (Figure 2) has been rather systematically obtained after multiple visits to the ridge top over the past eleven years. During the initial inspection of the area the large unifacial ferruginous siltstone scraper (U) was found in a tilled patch of okra downslope and south of the main scatter. All other artifacts were within the boundaries shown on the aerial photograph. My last visit to the site area was during the late summer of 2021. At that time the place had been allowed to revert to wild vegetation and the site area was covered in a small stand of cane.

Figure 2. Artifacts collected at Dry Branch; conjoinable objects are in black squares. The medial portion of a small, finely chipped Hamilton or elongate Madison arrow point (two conjoinable fragments) of tan/gray chert is Mississippian in age. Dating of nearby sites (Pleasant Run 40HM2, Ames 40FY7, Denmark 40MD85) indicates a temporal range of ca. AD 1100-1300 (Hadley 2013, Mainfort 1992; Mickelson 2020). Other formal tools from the site include a large coarse-grained ferruginous sandstone (FeSS) mortar or “nutting stone” with a deep pit, two large well-made FeSS spokeshaves, a small steep-edged FeSS end scraper, a large unifacial FeSS scraper made on a primary decortication flake; a single utilized flake fragment was also recovered. Nearly all the debitage is locally available, fine-grained ferruginous siltstone (found at the base of the Claiborne formation, Figure 3; Thomas 1997). The limited number of parent blocks, high proportion of cortex on dorsal surfaces, and high percentage of conjoinable fragments in the small assemblage indicate a very short-term, limited activity site. No aboriginal pottery has been recovered from the site surface. Other than the chert arrow point, all the chert debitage from the site appears to be from a single, small black pebble. The activities of a single family, which included primary subsistence tasks such as processing hickory nuts, preparing deer skins, spotting game, and crafting and maintaining hunting equipment, are reflected in the durable material remains.

Figure 3. An exposure of layered ferruginous conglomerate and sand along a tributary in the Gulf Coastal Plain. Dry Branch is within the day-trip radius of Pleasant Run, a ca. 13th century mound complex on the southwest side of the Hatchie River (orange circle in Figure 4). Approximately forty-five other archaeological sites of variable size and density have been identified in the same area, and many of them reflect the same kinds of ancillary activities and “content homogeneity” we should expect under conditions of reduced mobility and investment in a large and complex village and mound complex. Specifically, the sites reflect the same parochial use of locally available ferruginous stone, and the sites exhibit a consistent high ratio of this material to the more fine-grained silicious chert. Analysis of these archaeological places with the same level of detail that has been employed at Dry Branch would doubtlessly reveal some interesting intersite variability in the specific 13th century activities that were undertaken on the outskirts of the Pleasant Run village and mound complex.

Figure 4. The Hardeman County portion of Myer’s 1923 “Archaeological Map of the State of Tennessee.” The orange circle is the typical 10-km day trip radius around the Pleasant Run Mound complex. As noted in the discussion of the archaeological record in the larger West Tennessee region (see post on “Blakemore” September 2, 2022; Childress 2021: Childress et al. 1999; Smith 1979), the Hatchie River manifests as a temporally deep geophysical boundary marker. It is likely that small discrete “family places” like Dry Branch were part of a larger network of sites with affiliations to the west and southwest that extended to the margins of the loess bluffs bordering the Mississippi River alluvial belt and the upper Yazoo Basin. Research thus far indicates that the occupation of the region in the 12th and 13th centuries marked the terminus of intensive settlement and earthwork construction. After this time more concentrated site clusters are recorded closer to the larger channels of the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers.

This is where they walked, swam

Hunted, danced and sang

Take a picture here

Take a souvenir— REM (Cuyahoga)

Acknowledgements: Satin Platt of the Tennessee Division of Archaeology in Nashville assisted in researching the assemblage characteristics of other sites in the vicinity of Dry Branch. James Elliott providing lodging and a stimulating environment during my numerous trips to the site area.

References Cited

Ball, D.B. (editor and compiler). 2014. William Edward Myer’s Stone Age Man in the Middle South and Other Writings. Borgo Publishing, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Binford, L.R. 1980. Willow Smoke and Dog’s Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation. American Antiquity 45:4–20.

Binford, L.R. 1982. The Archaeology of Place. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1:5–31.

Binford, L.R. 1983. Long Term Land Use Patterns: Some Implications for Archaeology. In Lulu Linear Punctated: Essays in Honor of George Irving Quimby, edited by R.C. Dunnell and D.K. Grayson, pp. 27–53. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 72. Ann Arbor.

Childress, M.R. 2021. Blakemore Mounds (40GB206) and the Late Archaic–Middle Woodland Archaeological Record of West Tennessee. https://alabama.academia.edu/MitchellChildress

Childress, M.R., G.G. Weaver, and M.E. Starr. 1999. Discussion. In Archaeological Investigations at Three Sites near Arlington, State Route 385, Shelby County, Tennessee, compiled by G.G. Weaver, pp. 140-179. Tennessee Department of Transportation Environmental Planning Office Publications in Archaeology No. 4. Nashville.

Hadley, S.P. 2013. Multi-Staged Research at the Denmark Site, A Small Early-Middle Mississippian Town. Master’s thesis, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Memphis.

Mainfort, R.C., Jr. 1992. The Mississippian Period in the Western Interior. In The Obion Site: A Mississippian Center in Western Tennessee, by E.B. Garland, pp. 203-208. Report of Investigations 7. Cobb Institute of Archaeology, Mississippi State University, Starkville.

Mickelson, A.M. 2020. The Mississippian Period in Western Tennessee. In Cahokia in Context: Hegemony and Diaspora, edited by C.H. McNutt and R.M. Parish, pp. 243–275. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Myer, W.E. 1928. Indian Trails of the Southeast. In Forty-Second Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1924–1925, pp. 727–857. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington.

Smith, G.P. 1979. Archaeological Surveys in the Obion-Forked Deer and Reelfoot-Indian Creek Drainages: 1966 through early 1975. Memphis State University, Anthropological Research Center, Occasional Papers No. 9.

Thomas, D.W. 1997. Soil Survey of Hardeman County, Tennessee. USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service in cooperation with the Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station.

-

Evidence of Dalton Occupation along the St. Francis River, Greene County, Arkansas

Recent archaeological investigation of a small parcel in the Malden Plain of eastern Greene County, Arkansas turned up some limited but fairly interesting surface evidence for Dalton period (ca. 8500-7900 BC) occupation of natural levees and small islands at the head of a side tributary of the St. Francis River (Childress et al. 2019). Our fieldwork demonstrated that prehistoric lithic artifacts were discontinuously distributed on slightly elevated sand and silt deposits within an extensive flat of heavy clay soils (Figure 1; distributions after Fowlkes 2006; Robertson 1969). Six higher density nodes of surface material on the edge of the bottom, ranging in size from approximately 100 to 4,500 square meters, were recorded as sites 3GE522–3GE527. Artifacts, which included diagnostics from several different time periods, were restricted to the plowzone, and extensive shovel testing of the landforms failed to provide evidence of intact midden or features at any of the site locations.

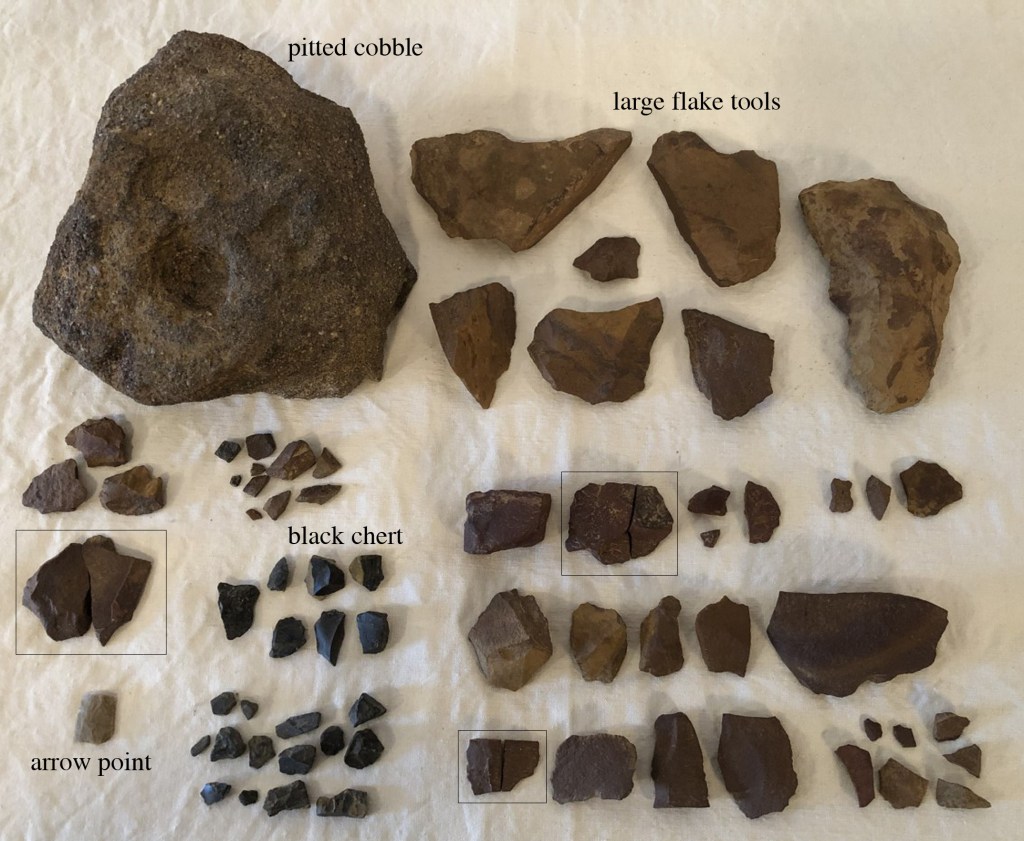

Figure 1. Soil distribution on the western margin of the St. Francis (1994 satellite imagery during period of very high water). While the surface collections contained no classic Dalton projectile points, several unifacial and bifacial tools, along with a fairly distinctive modified cobble, are considered signatures of Late Paleoindian occupation of the floodplain margin (Figure 2).

A lanceolate form biface (Figure 2c) found at 3GE522 does not strictly conform to any defined Paleoindian point type and lacks the characteristic pronounced basal concavity, thinning, or grinding of many early projectile points. However, Sam McGahey (2000:27-31) has described morphologically similar specimens from northern Mississippi as Lanceolate Dalton, citing Carl Chapman’s (1948) original definition of the type based on material from southeast Missouri. In a recent summary of the North American Paleoindian record, David Anderson (2014:917) points out that comparable unfluted lanceolate shaped bifaces have been documented in pre-Clovis, Dalton, and later Paleoindian contexts in several localities. Additionally, it is a well-made point and is knapped from an exotic-looking, sugary piece of banded orthoquartzite that contains small lenticular chert inclusions. Several small step fractures on both faces indicate that the raw material block or cobble was challenging to reduce, so it was apparently made by a very skilled knapper. Although it may be exotic to the local area, similar raw material is reportedly found in the cobble deposits of nearby Crowley’s Ridge (McCutcheon and Dunnell 1998; Morse 1997:15).

Figure 2. a: quartzite cobble tool (3GE527), b: large exotic chert flake (3GE527), c: Lanceolate Dalton point (3GE522), d: large flake tool (3GE523), e: endscraper (3GE524), f: blade tool (3GE522), g: endscraper (3GE524) [photograph by Kate Gillow] Several well-made unifacial tools, including two formal endscrapers (Figure 2e and g) and an edge-modified small blade (Figure 2f) were all struck from relatively small cobbles of tan gravel that were probably also obtained from the short streambeds draining Crowley’s Ridge. All of these tools have remnant cortex on the dorsal face (the primary working edge of the tools is on the bottom margin as shown in the photograph) clearly indicating that they were made on primary or secondary decortication flakes. The largest of the unifaces (Figure 2d) still retains a sharp, low-angled working edge that must have been used more for slicing than scraping. One of the formal endscrapers from 3GE524 (Figure 2g) may have also had a graver spur on one side. No spokeshaves or utilized pièce esquillées, characteristic of assemblages of comparable antiquity, were found on the site surfaces. Nearly identical unifacial tools have been described from the Sloan site (Morse 1997), located about 35 km due west of the site area on the opposite side of Crowley’s Ridge.

In addition to the more formal unifacial tools, a single large flake of extremely high-quality, waxy brown and black banded chert may have been brought to the local area during the Dalton occupation (Figure 2b). While there are indications of light use on one of the sharper edges of this flake, it was not significantly modified after detachment. There is one small area of very thin cortex on the dorsal surface immediately opposite the bulb of percussion, but it is not much different in color or appearance than the interior of the stone. This flake may thus have been struck from a quarried tabular block rather than a stream cobble. Our recent work with a large collection of chipped stone from a rockshelter in Newton County, Arkansas leads us to conclude that this raw material is not found in the limestone formations of the Ozarks, and it is not remotely similar to any of the specimens shown in the color plates of Jack Ray’s (2007) lithic raw material guide for that region. While exotic chert is certainly not diagnostic of any particular temporal interval, transport of high-quality raw material over great distances is a hallmark of highly mobile Paleoindian foragers.

Finally, a fairly unusual edge-abraded cobble (244.8 grams) of coarse-grained quartzite recovered from 3GE527 (Figure 2a) is also considered to be a Dalton-era artifact (cf. Morse 1997:44-51; Figure 3.16f). The cortex of the cobble, which is extremely smooth and water-worn, is missing from nearly the entire perimeter, but the exposed granular interior of the piece does not exhibit any well-defined negative flake scars. Removal of the cortex thus may have been accomplished by controlled heat crazing rather than direct percussion (the outer zones of the stone are redder than the interior, possibly due to heat treatment). The most extensive use of the coarse edge is on the lower portion as shown in the photograph. The cobble also has a shallow pit on one surface (down in the photograph) that suggests multi-functional use as a bipolar anvil stone. Running across the bipolar pit are a series of extremely shallow, very closely spaced parallel grooves or striations oriented along the long axis of the stone. It is not clear what kind of action produced these faint but distinctive marks, but platform preparation of a biface margin is certainly a possibility. This multi-functional artifact seems to correspond to one of the “bewildering array” of Dalton-era cobble tools described for this portion of the Mississippi Valley (Morse and Morse 1983:71-80).

None of the artifacts found during the recent survey work, when considered in isolation, would have provided enough evidence to postulate the occupation or use of this portion of the St. Francis Basin during the Late Paleoindian period. However, taken together and situated within the significant body of previous and ongoing research regarding the earliest portion of the North American archaeological record, the stone tools may be used to make a fairly strong case for the identification of land use here in the period ca. 12,500 to 11,000 cal. BP. Significant density of earlier Paleoindian foragers in this portion of the Central Mississippi Valley is clear from the distribution of Clovis and related fluted point types, with 35 percent of the state’s total mapped in Greene, Craighead and Clay counties alone. This density apparently continues into adjacent portions of the Malden Plain near Crowley’s Ridge (O’Brien and Wood 1998; Morrow 2006, 2019). Given the clear and mounting evidence for pre-Clovis occupation of the continent (e.g., Fagundes et al. 2008), we may infer that the earliest foragers entered the region many centuries, and perhaps millennia, before the advent of distinctive fluted point technology. From this ancient base the well-documented Dalton groups of the region developed. It seems significant that the locale reported herein, at the head a small tributary near a section of swampy land in a setting very similar to the nearby Sloan site, is within one of the postulated Dalton band areas along this stretch of the St. Francis River. The mapped extent of the foraging catchment covers about 3,000 km2 and is centered on a “reported major concentration” of Dalton material found about 27 km to the northeast of the project area in the vicinity of White Oak Ridge in extreme northeastern Greene County (Morse 1997:123-139; Morse and Morse 1983:Figure 4.1).

Original citation: Childress, M.R., and C.A. Buchner. 2020. Evidence of Dalton Occupation along the St. Francis River, Greene County, Arkansas. Field Notes, Newsletter of the Arkansas Archeological Society 412:7-10.

References Cited

Anderson, D.G. 2014. Paleoindian and Archaic Periods in North America. In The Cambridge World Prehistory, edited by P. Bahn and C. Renfrew, pp. 913-932. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Chapman, C.H. 1948. A Preliminary Survey of Missouri Archaeology, Part IV. Missouri Archaeologist 10(4):135-164.

Childress, M.R., C.A. Buchner, and A. Saatkamp. 2019. Archaeological Survey of the Big Island and Below Piggot/Nimmons Borrow Areas, St. Francis Maintenance and Supplemental Seepage Remediation Project, Clay and Greene Counties, Arkansas. Panamerican Consultants, Memphis. Report submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Fagundes, N.J.R., R. Kanitz, R. Eckert, A.C.S. Valls, M.R. Bogo, F.M. Salzano, D.G. Smith, W.A. Silva, Jr., M.A. Zago, A.K. Ribeiro-dos-Santos, S.E.B. Santos, M.L. Petzl-Erler, and S.L. Bonatto. 2008. Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas. The American Journal of Human Genetics 82:583-592.

Fowlkes, D.H. 2006. Soil Survey of Greene County, Arkansas. USDA, Soil Conservation Service in cooperation with the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

McCutcheon, P.T., and R.C. Dunnell. 1998. Variability in Crowley’s Ridge Gravel. In Changing Perspectives on the Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley, edited by M.J. O’Brien and R.C. Dunnell, pp. 258-280. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

McGahey, S.O. 2000. Mississippi Projectile Point Guide. Mississippi Department of Archives and History Archaeological Report No. 31. Jackson.

Morse, D.F. 1997. Sloan: A Paleoindian Dalton Cemetery in Arkansas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Morse, D.F., and P.A. Morse. 1983. Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. Academic Press, New York.

Morrow, J. 2006. The Paleoindian Period in Arkansas, between approximately 13,500 and 12,620 calendar years ago. Field Notes No. 331:3-9. Arkansas Archeological Society.

Morrow, J. 2019. What is a Sloan Point? Field Notes No. 410:8-13. Arkansas Archeological Society.

O’Brien, Michael J., and W. Raymond Wood. 1998. The Prehistory of Missouri. University of Missouri Press, Columbia.

Ray, J. H. 2007. Ozarks Chipped Stone Resources: A Guide to the Identification, Distribution, and Prehistoric Use of Cherts and Other Siliceous Raw Materials. Special Publication No. 8. Missouri Archaeological Society, Columbia. Robertson, N.W. 1969. Soil Survey of Greene County, Arkansas. USDA, Soil Conservation Service in cooperation with the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

-

Vesicular Abraders from the Ohlendorf Site

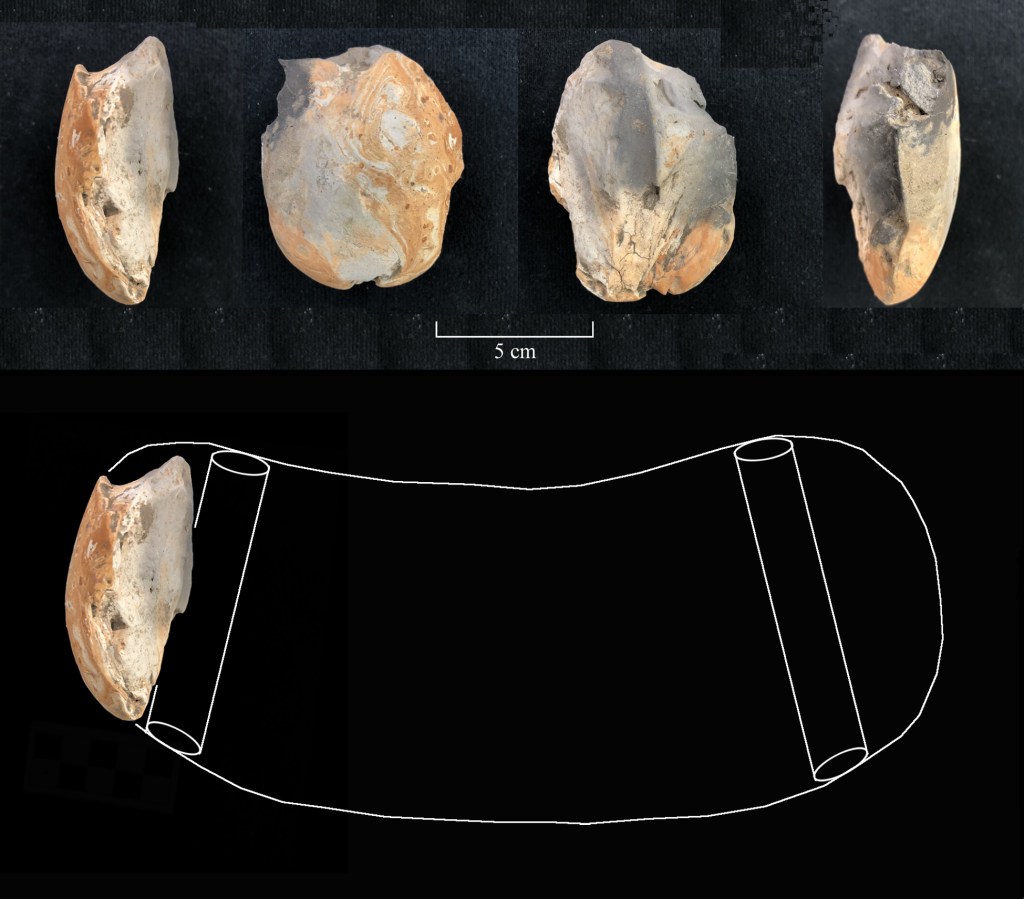

In addition to the loom weight fragments described in an earlier post (Prehistoric Textile Production, September 5th, 2022) eight porous stone artifacts recovered from the surface and upper portions of the archaeological deposit at Ohlendorf are also of particular interest (Figure 1, Table 1). The objects are primarily shades of grey, yellow-brown, and pink, and are characterized by abundant surface vesicles, rough texture, and very low density. The largest of the stones, recovered from the upper 40 cm of the site deposit, is very low density and floats on the surface of water. None of the other pumice-like stones floated, but this could be related to the filling of the smaller near-surface vesicles with heavier soil particles and sand grains. One of the artifacts had a deep longitudinal groove on one side and all the artifacts, most of which seemed to be fragments, had evidence of use as hand-held abraders. The abrasive stone was apparently employed in weapon shaft and bone tool manufacture, hide preparation, and was occasionally carved into pipe bowls and pendants. This distinctive raw material, which we initially considered to be pumice stone, is uncommon in the locale of investigation and has not, to our knowledge, been previously described as part of Late Mississippian assemblages in the northern Nodena phase area (but see Morse 1989:Figure 9l). At Banks Village (3CT13), 40 km southwest of Ohlendorf near Lake Wapanocca, Perino (1966:55; Figures 17 and 24) recovered several abraders and a bead-like object that we believe are the same raw material (the illustrated “floatstone” abrader from 3CT13 is 6.0 cm long).

Figure 1. Vesicular abraders from Ohlendorf. Table 1. Ohlendorf (3MS796) vesicular stone artifacts.

Color L, mm W, mm TH, mm Vol, cubic mm Mass, g Density, g:cubic mm dark gray 64.6 47.3 36.6 111834.2 42.7 0.000382 grayish brown 41.4 28 23.3 27009.4 15.8 0.000585 dark gray, grayish brown 49.9 31 16.3 25214.5 18.4 0.00073 pink 48.1 30.6 14.2 20900.4 15.5 0.000742 grayish brown 30.5 23.8 20.2 14663.2 11.2 0.000764 dark gray 23.2 23.7 16.4 9017.4 7.2 0.000798 dark gray, very pale brown 45.4 24.8 20.1 22631 18.8 0.000831 gray, yellow-brown 69.5 33.2 28.4 65530.2 57.6 0.000879 L, length; W, width; TH, thickness; Vol, volume Identical artifacts have been described on numerous archaeological sites to the north and northwest of Ohlendorf along the Missouri River drainage between South Dakota and the confluence of the Mississippi River (Estes et al. 2010; Stephenson 1971:69, Plate XXXIIa-e). Referred to more correctly as paralava, this porous light-weight stone occurs where naturally combusted near-surface coal seams have baked and physically modified surrounding sedimentary materials. Subsequent erosion washes chunks of the paralava into regional drainages, where some of it travels downstream as low-density “floatstone” and accumulates with driftwood and other light-weight materials on islands and bars along the channel (see discussion by Perino 1966:55). A large paralava outcrop is mapped in southwestern North Dakota and eastern Montana, where the main upper Missouri River tributaries (Cannonball, Heart, Yellowstone, and Knife Rivers) cut through the metasedimentary surface exposures. Volcanic sources of igneous pumice and tuff also outcrop farther upstream in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, but physical and chemical analysis of vesicular artifacts from the Leary site in southeastern Nebraska indicated clearly that they are made of metasedimentary paralava rather than true volcanics (Estes et al. 2010:75-76).

No chemical analysis of the Ohlendorf vesicular artifacts was performed, but several lines of evidence strongly suggest that this material is also paralava and was probably collected locally as “floatstone” from driftwood dams and sand bars along the main channel of the Mississippi River, located only about two km east of the site. The qualitative color range of the abrasive stone artifacts from Leary and Ohlendorf is the same (cf. Estes et al. 2010:72 and Table 2), and the density of the material as calculated from the arithmetic means of the quantitative ranges of the two samples is essentially identical (Table 2; unit is g per cubic mm). Furthermore, the Ohlendorf artifacts are about 20–28 percent smaller than the Leary sample (n = 13), which is within expectations given the gradual reduction in size due to stream-action erosion as a direct function of distance from the source outcrop. In fact, the maximum size of the Ohlendorf artifacts is quite accurately predicted by a simple linear distance-decay function which can be generated from data provided by Estes and colleagues (2010:77), who state that the maximum dimension of paralava artifacts from the Steed-Kisker sites is 9.5 cm compared to 9.81 cm at Leary, located ca. 92 km (straight-line distance) upstream (reduction of 0.00337 cm/km). Ohlendorf is in turn about 765 km downstream from Steed-Kisker and should thus exhibit a maximum artifact dimension of 9.5 – [(0.00337)(765)] = 6.92 cm. The longest artifact found at Ohlendorf was 6.95 cm (Table 2, column 3, bottom). At Potts Village (ca. AD 1550–1700), located upstream 700 km north-northwest of Leary along the Missouri River just south of the paralava outcrop, Stephenson (1971) recovered 44 “scoria” specimens with a maximum dimension of 10.5 cm, somewhat less than the value of 12.1 cm predicted by the linear function.

Table 2. Quantitative comparison of Ohlendorf and Leary site paralava artifacts.

Site Mass, g L range, mm W range, mm Th range, mm Mean density Leary (25RH1) 2.7-152.2 30.0-98.1 16.2-72.2 9.9-59.6 0.000787 Ohlendorf (3MS796) 7.2-57.6 23.2-69.5 23.7-47.3 14.2-36.6 0.000775 L, length; W, width; TH, thickness Apart from the Banks Village specimens reported by Perino (1966:55), we are unaware of similar paralava artifacts in regional assemblages of the late prehistoric Nodena, Tipton, Walls, or Horseshoe Lake phases. A vesicular grooved abrader with a maximum dimension of 5.8 cm from the Upper Nodena site (Morse 1989:Figure 9l) may also be paralava, but no detailed discussion of the raw material accompanies the artifact plate. “Pumice abraders” have been identified very near the Mississippi River in the Cairo Lowlands at the chronologically earlier Weems and Hoecake sites (Williams 1974). No dimensions or illustrations of the artifacts are included in the site report, but the linear function described above predicts that these artifacts should be slightly larger than the Ohlendorf specimens, with a maximum dimension of about 7.35 cm. As pointed out in the excellent article on this distinctive material class (Estes et al. 2010:77), early observers such as George Catlin recognized that paralava was likely located “in every pile of driftwood from [the outcrop] to the ocean,” so it is assumed that these artifacts are under-reported in the technical literature, particularly from archaeological sites very near the main Mississippi River channel below the mouth of the Missouri. While paralava is documented from sites as early as the Archaic horizon, it seems to be more prevalent on very late prehistoric sites. Ohlendorf, with three calibrated median radiocarbon dates between AD 1419 and 1568, further reinforces this temporal trend (Buchner et al. 2022).

References Cited

Buchner, C.A., M.R. Childress, J. Rossen, and A. Baer. 2022. Phase I Cultural Resources Survey of the 2401.79-Acre Exploratory Ventures LLC Proposed Project in Mississippi County, Arkansas. Commonwealth Heritage Group/Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Estes, M.B., L.W. Ritterbush, and K. Nicolaysen. 2010. Clinker, Pumice, Scoria, or Paralava? Vesicular artifacts of the Lower Missouri Basin. Plains Anthropologist 55(213):67–81.

Morse, D.F. (editor). 1989. Nodena: An Account of 90 Years of Archaeological Investigation in Southeast Mississippi County, Arkansas. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 30 (second edition).

Perino, G. 1966. The Banks Village Site, Crittenden County, Arkansas. Missouri Archaeological Society Memoir No. 4, Columbia.

Stephenson, Robert L. 1971. The Potts Village Site (39CO19), Oahe Reservoir, North Central South Dakota. The Missouri Archaeologist 33:1–140.

Williams, J. R. 1974. The Baytown Phases in the Cairo Lowland of Southeast Missouri. The Missouri Archaeologist 36:1–109.

-

Evidence of Late Prehistoric Textile Production from the Central Mississippi River Valley

Abstract. Recent work at two archaeological sites, Ohlendorf (3MS796) and Edmondson Farmstead (3CT73), in the lowlands of eastern Arkansas have produced artifacts and faunal remains that are associated with the production of textiles. Unusual baked clay artifacts that appear to be loom weights have been recovered along with ceramic disc spindle whorls from several sites in the region. The recovery of the nearly complete skeleton of a mature opossum, combined with ethnographic descriptions of the production of opossum fur fibers, suggests these animals may have been kept as raw material sources.

From a controlled surface collection of artifacts obtained from the ca. AD 1300-1600 Ohlendorf site (Buchner et al. 2022), an unusual artifact fragment was recovered (Figure 1). It is made of varicolored clay and seems to be constructed of two layers: an inner massive core which is fairly homogeneous in structure and an outer thinly laminated swirled coating that is about 4–5 mm thick. The clay has a raspy texture and is tempered with very fine sand throughout. The inner core is gray and white, while the thinner outer coating is mostly pale gray and orange. On the interior of the object is approximately 20 percent of a perfectly cylindrical channel or hole that would have had a diameter of about 1.7 mm. There are no impressions on the channel, suggesting that the clay was formed around a very smooth object such as a joint of river cane. The artifact has a volume of about 26.5 cm3 and a mass of 81.5 g. It is thought to be the end of a large, symmetrical loaf-shaped fired clay artifact with two perforations as shown in the lower panel of Figure 1. Another part of the same object (non-conjoinable) and two other even more fragmentary coarse shell tempered specimens with similar channels were recovered from the Ohlendorf site surface.

Figure 1. Perforated baked clay object fragment from Ohlendorf. The hypothesized reconstruction of the complete artifact from the Ohlendorf fragment is based on an item of apparently identical form originally brought to my attention in the spring of 1993 (Figure 2). The fired clay object has a volume of about 930 cm3 and a mass of 2850 g. It was then among a collection of prehistoric site materials assembled by a Dr. Daniel A. Buechner, III of Memphis, Tennessee. The site, labeled by Dr. Buechner as “A3,” was not located on a map, but other material from the surface collection included two large rim sherds of Barton Incised, var. Togo, six rims of Barton Incised, var. Barton, four pieces of Mississippi Plain, var. Neeley’s Ferry (1 bowl rim, 1 bottle neck, 2 jar lugs), three sherds of Parkin Punctated, one sherd of Walls Engraved, one sherd of Old Town Red, and a large fragment of cane-impressed daub. Identified sites from which other materials had been obtained were Rose Mound and Parkin on the Lower St. Francis; Walls, Lake Cormorant, Irby, and Withers south of Horn Lake in northwest Mississippi; and Mound Place in eastern Crittenden County, Arkansas. Based on the diagnostic ceramics, the geographic range of the identified sites, and the occurrence of similar loaf-shaped artifacts, we feel confident that the Buechner “A3” collection is probably from a Late Mississippian site (ca. AD 1000-1550) in the Walls, Horseshoe Lake, or southern Nodena phase areas.

Figure 2. Late Mississippian perforated baked clay object from the Memphis region, Buechner collection (photographs by Candace Spearman). An object almost identical to the Buechner specimen was excavated in 1957 by Gregory Perino (1966) at the Banks Village site (Figure 3, right panel). The Banks Village artifact, which Perino considered to be of “doubtful utility” but speculated may have been a “pottery support,” lacks perforations but does have portions of a cord groove on the convex surface parallel to the long axis (cf. Figure 2, top). Both items also had remnant fabric markings on the exterior. Another perforated clay object and a flare-ended clay bar (Figure 3, left) were recovered within one of the houses. The Banks Village site also yielded several spool-shaped clay artifacts for which no function was hypothesized.

Figure 3. Unusual baked clay objects from Banks Village (3CT13) (Perino 1966: Figures 31 and 32). The Lawhorn site (3CG1), located about 50 km northwest of Ohlendorf on the St. Francis River, also yielded several similar fired clay objects, one of which contained a large central perforation that Moselage (1962:61; Figure 27-1) speculated may have functioned as a loom weight. Another unillustrated fired clay specimen is described as containing a groove around a portion of the margin and another with “a coarse textile impression on one side and a surface well smoothed on the other.” These details both occur on the complete perforated object from Dr. Buechner’s site A3 (Figure 2). In addition to the possible loom weight fragments, the Lawhorn site yielded 27 perforated sherd disc spindle whorls that ranged in size from 3 to 8 cm in diameter, attesting to the importance of fiber production at the site. The spindle whorls were mainly associated with the excavated house floors (Moselage 1962:44; 69-80; see Alt 1999 for detailed discussion of Mississippian spindle whorls and fiber production). The Ohlendorf controlled surface collection contained only two unperforated ceramic sherd discs, but extensive archaeological research at the site would doubtlessly provide additional evidence of fiber production and textile manufacture.

In agreement with Moselage, we consider all the unusual baked clay objects recovered from Ohlendorf, Banks Village, and Lawhorn to be loom weights. They match the descriptions and morphology of Old-World examples remarkably well (see Gleba and Cutler 2012; Mårtensson et al. 2009), but appear to have been too massive and bulky for use on groups of warp threads as would have been employed on a hanging warp-weighted loom (see Lipo et al. 2011:Figure 8). The range of spindle whorl sizes recorded at late period sites in the region suggest quite a range of thread sizes from fine to rather coarse (the Ohlendorf sherd discs had weights of 13.2 g and 31.5 g, which would have produced thick yarn threads in the 4–9 mm size range if used as spindle whorls). If these large, fired clay objects are loom weights, they were probably hung from a lower bar on which the bottoms of the individual warp threads were attached. More insight could be provided through replication study.

An unusual opossum burial from the contemporaneous Edmondson Farmstead site (3CT73; Childress et al. 2022) provides additional indirect evidence for the importance of fiber and textile work in the region. The intentionally interred skeleton was nearly complete and tooth wear indicated that the animal was quite old; these unusual marsupials have a very short life span and rarely survive for more than about two years in the wild. While they are certainly documented as food sources their frequencies in faunal collections are usually below what would be a expected given their population density and ease of capture. Swanton (1946) provides several ethnographic examples of the use of opossum fur for the production of fibers and textiles, and the 3CT73 specimen indicates that the animals may have been kept in village areas as a ready source of fur.

References Cited

Alt, S., 1999. Spindle Whorls and Fiber Production at Early Cahokian Settlements. Southeastern Archaeology 18(2):124–134.

Buchner, C.A., M.R. Childress, J. Rossen, and A. Baer. 2022. Phase I Cultural Resources Survey of the 2401.79-Acre Exploratory Ventures LLC Proposed Project in Mississippi County, Arkansas. Commonwealth Heritage Group/Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Childress, M.R., J. Rossen, C.A. Buchner, and A. Baer. 2022. Archaeology at Edmondson Farmstead (3CT73), Crittenden County, Arkansas. Commonwealth Heritage Group/Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Gleba, M., and J. Cutler. 2012. Textile Production in Bronze Age Miletos: First Observations. In Kosmos: Jewellery, Adornment, and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age, edited by Marie-Louise Nosch and Robert Laffineur, pp. 113–121. Peeters Leuven, Liege.

Lipo, C.P., T.D. Hunt, and R.C. Dunnell. 2011. Formal Analyses and Functional Accounts of Groundstone “Plummets” from Poverty Point, Louisiana. Journal of Archaeological Science, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.004.

Mårtensson, L., M. Nosch, and E.A. Strand. 2009. Shape of Things: Understanding a Loom Weight. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 28(4):373–398.

Morse, D.F. (editor). 1989. Nodena: An Account of 90 Years of Archaeological Investigation in Southeast Mississippi County, Arkansas. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 30 (second edition).

Moselage, J. 1962. The Lawhorn Site. The Missouri Archaeologist 24:1–110.

Perino, G. 1966. The Banks Village Site, Crittenden County, Arkansas. Missouri Archaeological Society Memoir No. 4, Columbia.

Swanton, J.R. 1946. The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 137. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Williams, J. R. 1974. The Baytown Phases in the Cairo Lowland of Southeast Missouri. The Missouri Archaeologist 36:1–109.

-

Long-Term Demographic Trends Reflected in the Archaeological Record of Central Louisiana

Abstract: Primary archaeological data drawn from the interfluvial region between the Calcasieu and Red Rivers in South Central Louisiana are summarized and compared to radiocarbon proxy measures of regional demographics in the greater southeast. Although the long-term growth rate for the region is calculated at 0.06–0.07% based on the diagnostic projectile point and radiocarbon date data, it is estimated that a complete review of the regional radiocarbon record would indicate a more modest growth rate in the 0.03–0.05% range. Variation in the spatial density of radiocarbon dates suggests aboriginal population densities within linear riparian zones were roughly 5 to 6 times those maintained in the flanking uplands. The upland interfluvial zones where most of the Kisatchie National Forest ranger districts are located would certainly fall into the lowest density category. The broad picture of archaeological site and isolated find density developed from systematic fieldwork on Kisatchie National Forest parcels is highly concordant with the larger regional spatial and temporal patterns.

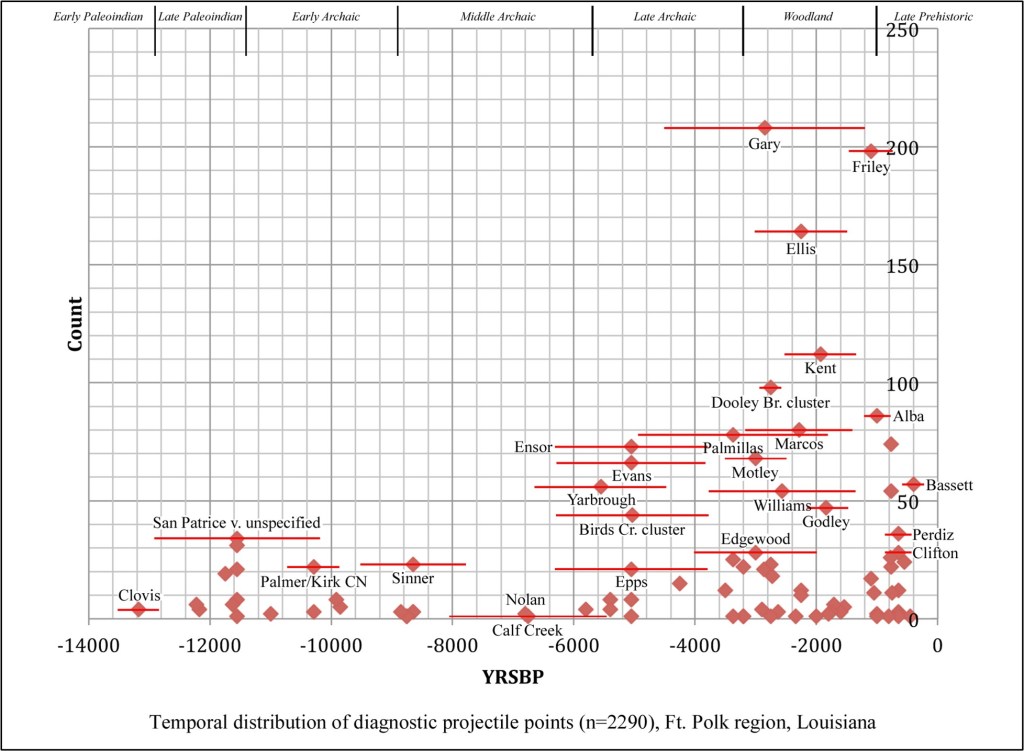

Review of the prehistoric cultural-historic sequence of highlights the close relationship of the central Louisiana archaeological record to the developing picture of Late Pleistocene through Holocene aboriginal occupation in the broader southeastern and mid-continental U.S (Childress and Saatkamp 2021). The early antiquarian and pre-radiocarbon era professional investigations have been significantly augmented during the past four decades by compliance related archaeology conducted within the boundaries of the various Kisatchie National Forest (KNF) ranger districts and regional military installations. The modern cultural resources management work has been particularly robust from a research standpoint because the examined landscapes have approached what might be considered a truly random sample, rather than a biased series of tracts containing high-profile sites that might be expected to yield the maximum amount of desirable, museum-quality artifacts. This is a distinct scientific advantage, but it is accompanied by a daunting challenge for anyone wishing to synthesize and summarize a small mountain of systematic data that is dispersed across a multitude of agencies, institutions, and private sector concerns. One of the most comprehensive synthetic treatments of the interfluvial region between the Red and Calcasieu drainages is based on the work done at Ft. Polk (Vernon and Sabine parishes; Anderson and Smith 2003). A comparable summary for findings in the various KNF districts would be a significant augmentation to regional research. Information on long-term trends revealed by the various Ft. Polk investigations is summarized in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1. Diagnostic projectile points and suggested temporal spans, Ft. Polk, Louisiana.

Period Span BP midpoint Years PP/K Count PP/Ks/year STD STD % Late Prehistoric 1000-200 BP 600 800 667 0.834 114.64 0.538 Woodland 3200-1000 BP 2100 2200 829 0.377 51.81 0.243 Late Archaic 5700-3200 BP 4450 2500 464 0.186 25.52 0.12 Middle Archaic 8900-5700 BP 7300 3200 148 0.046 6.36 0.03 Early Archaic 11,450-8900 BP 10175 2550 77 0.03 4.15 0.019 Late Paleoindian 12,900-11,450 BP 12175 1450 101 0.07 9.58 0.045 Early Paleoindian 13,450-12,900 BP 13175 550 4 0.007 1 0.005 TOTALS 2290 213.06 BP-years before present (1950); PP/K-projectile point/knife; STD-standardized (PP/Ks/year/0.007) In considering the disaggregated data on the frequency, temporal slotting, and approximate use-spans of various diagnostic projectile points (Figure 1), several suggestive patterns are immediately apparent. The most obvious is the long-term exponential growth trend in the overall frequencies, with a dramatic increase beginning in the post-Hypsithermal Late Archaic. It is particularly noteworthy that the Ft. Polk data show this trend continuing to the terminal portion of the late prehistoric interval, in line with expectations that would be derived from a consideration of demographic patterns based on a relatively stable but modest pre-industrial growth rate (ca. 0.03–0.05%; Bettinger 2016). This consistency appears to be directly related to the fact that the diagnostic weapon tips are derived almost exclusively from systematic shovel and test unit excavations rather than surface collections from agricultural fields (the latter sample types, quite common in alluvial settings, are particularly biased against the recovery of small, late period arrow points, and the spurious indication of “decline” generated by consideration of biased surface collections has more than occasionally been employed as evidence for late prehistoric population growth rate/density reductions or “migrations”). During the earlier pre-ceramic intervals, the significant representation of San Patrice variants and what appears to be a muted Middle Archaic presence in the region are also reflected in the distribution.

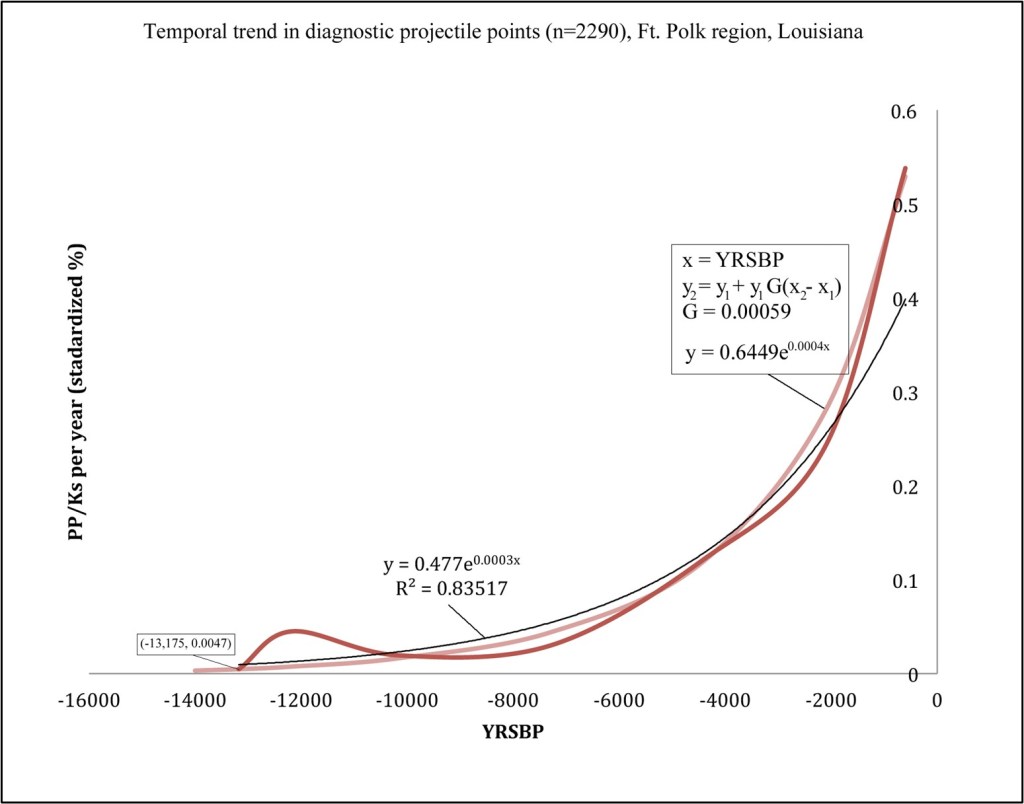

Figure 1. Suggested mid-points and spans for diagnostic projectile points recovered at Ft. Polk, Vernon and Sabine Parishes, Louisiana (Anderson and Smith 2003: Table 5.1; 242–300). These primary data on the temporal distribution of stone tool diagnostics are collapsed and aggregated in Table 1 and Figure 2 (see also Anderson and Smith 2003:Figure 5.14). In addition to the rather typical adjustment for the duration of the period in question (PP/Ks per unit time), these ratios are further standardized by dividing each grouping by the smallest value (Early Paleoindian at 0.007). Calculating the proportion of the total of the standardized values (in this case 213.06) facilitates the comparison of this sample with others containing different numbers of diagnostics. The resulting plot allows for a coarse measure of demographic variability in the region of interest and points to some long-term trends that have also been elucidated in adjacent areas (and sheds considerable affirmative light on the question posed in the Ft. Polk summary: “can measures of local population density be developed . . . perhaps using numbers of diagnostic artifacts as a proxy measure for people” [Anderson and Smith 2003:363]?).

Figure 2. Smooth line plot of seven diagnostic projectile point group midpoints (red), fitted natural logarithmic function (black), and growth function (pink); see Table 1. Employing the divisions of the Fort Polk sequence suggests a clear exponential trend in regional demographics between the earliest occupation period and the onset of European exploration and settlement (Figure 2). Although the fitted line generated by the statistical component of the spreadsheet application (black) has a very high correlation coefficient, the algebraic growth function (pink) appears to visually accommodate the raw data trend in a slightly more convincing manner, particularly considering the nearly perfect overlap in the initial and terminal dependent variable values. These proxy data indicate a gradually increasing regional population with a growth rate of 0.00059 (0.059%). They also strongly suggest, along with other independent lines of evidence from the greater southeast, that the deviations indicated for the Late Paleoindian/Early Archaic (San Patrice) and Middle Archaic intervals should not be taken at face value to indicate either periods of “rapid growth” or “population decline.” This is certainly a possible explanation, but a stronger argument could probably be made that these are measures of variation in the relative intensity of local settlement and land use.

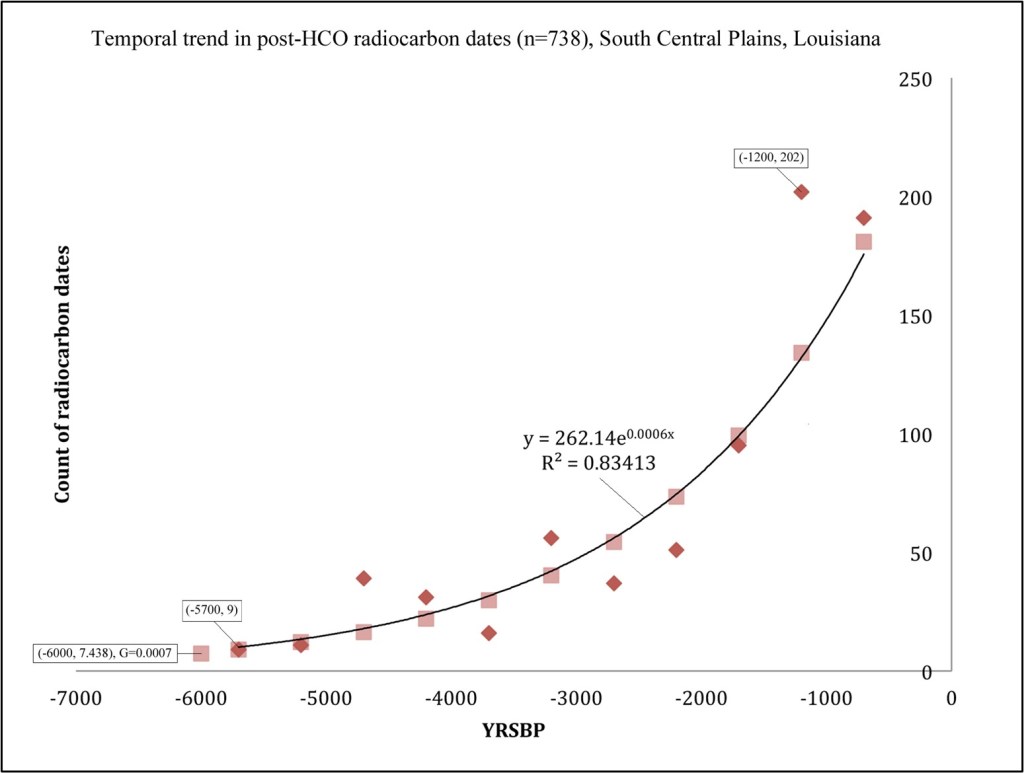

Figure 3. Point plot of eleven midpoints of calibrated radiocarbon group clusters, ca. 4000 BC–AD 1500 (red), fitted natural logarithmic function (black), and growth function (pink), northwest Louisiana and southwest Arkansas [data from Alvey 2019: Table 3.1]. Observations based on the relatively small Ft. Polk area contrast somewhat with the findings from the larger region (South Central Plains) summarized by Alvey (2019), whose summed probability distribution (SPD) plot of 297 radiocarbon dates was interpreted to reflect a demographic decline or geographic shift during the period post-dating ca. AD 1300. A larger clustered set of 738 calibrated assays (Figure 3) complements the demographic trend defined by the sample of Ft. Polk diagnostic projectile points, but for the post-Middle Archaic interval the estimated growth rate is somewhat larger (0.0007, 0.07%). Calculations based on various archaeological proxy measures and ethnographic sources (Table 2) indicate that both approximations of G for the central Louisiana region are probably somewhat inflated (growth functions are extremely sensitive to small differences in rates, particularly over the entire span of New World occupation). A more detailed consideration of the full suite of available radiocarbon dates would more than likely indicate a rate within the fairly narrow range of 0.03–0.05%. The post–6000 BP period considered by Alvey (2019) that includes northwestern Louisiana and southwestern Arkansas is also very closely aligned with the depth of the radiocarbon record at Ft. Polk, where the earliest assay has been obtained on organics from 16VN794 (Beta-49293, 5770 ± 140 BP, cal median 4629 BC; Anderson and Smith 2003: Table 6.2; earlier determinations from the area are based on TL and OCR measures).

Table 2. Various pre-industrial growth rate estimates based on demographic proxy measures and ethnographic data.

Region Sample G Reference Western Louisiana diagnostic PP/Ks 14,000-200 BP (6 intervals) 0.06% Anderson and Smith 2003 (data) Ozarks 193 calibrated radiocarbon dates 0.046 ± 0.0014% Childress 2021 Global radiocarbon dates/SPDs; ethnographic sources 0.043 ± 0.011% Zahid et al. 2016 Wyoming/Colorado 7900 calibrated radiocarbon dates 0.041 ± 0.003% Zahid et al. 2016 Global range – 0.03–0.05% Bettinger 2016 Southern Interior Low Plateau 702 calibrated radiocarbon dates 0.04% Childress 2021 Interior Low Plateau 7440 site components across various intervals (harmonic mean of 10 samples) 0.04% – Kentucky 7116 site components across 4 intervals (harmonic mean) 0.04% Pollack 2008 (data) SPD–summed probability distribution; G–growth rate in p2 = p1 + p1GY, Y = years between p1 and p2 Finally, with respect to regionally specific population density values, the radiocarbon record is also a valuable proxy measure for consideration, especially allowing for the valid assumption of comparable pre-industrial growth rates (Table 2). Based on date density across the full temporal range of archaeological site components, it is possible to reconstruct density variability between physiographic regions (Table 3). Not surprisingly, the highest density areas appear to have been in the central and lower Mississippi alluvial valley and along the lower reaches of the Tennessee and Cumberland drainages in the southern portion of the Interior Low Plateau (comparable values are probably registered to the north into the Green and Ohio River sections of the Interior Low Plateau, but these data have yet to be fully compiled). Radiocarbon date density suggests populations at roughly 5 to 6 times the density of the flanking uplands, with the Ozark Highlands and northern Missouri hill country at the low end of the range. The South Central Plains of northwestern Louisiana exhibit an intermediate value, but even here the majority of determinations have been obtained from sites within and close to the riparian zone along the Red River (see Alvey 2019:Figure 2.2). The upland interfluvial zones where most of the KNF ranger districts are located would certainly fall into the lowest density category. The broad picture of archaeological site and isolated find density developed from systematic survey on KNF parcels is highly concordant with the larger regional spatial and temporal patterns (for more generalized and comprehensive discussion of the prehistoric demography see Bettinger 1991 and Hassan 1981) .

Table 3. Information on radiocarbon date spatial density by region (Alvey 2019:20; Childress 2021).

Region Area (square km) N dates Density STD density Lower LMV Alluvial Plain (LA/MS) 30080 412 0.0137 12 Southern Interior Low Plateau (TN/MS/AL) 60600 702 0.0116 10 Upper LMV Alluvial Plain (AR/MO/KY/TN/MS) 68091 537 0.0079 7 Coastal Zone (LA/MS) 49239 294 0.006 5 South Central Plains (LA/AR) 81923 297 0.0036 3 MS/TN Highlands 129959 447 0.0034 3 AR/MO Ozark Highlands 69000 196 0.0028 2 AR Ozark Highlands 64782 182 0.0028 2 Central Dissected Hills (MO) 61534 142 0.0023 2 MO Ozark Highlands 94036 109 0.0012 1 STD–standardized (absolute density/0.0012) References Cited

Alvey, J.S. 2019. Paleodemographic Modeling in the Lower Mississippi River Valley. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Anderson, D.G., and S.D. Smith. 2003. Archaeology, History, and Predictive Modeling: Research at Fort Polk, 1972-2002. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Bettinger, R L. 1991. Hunter–Gatherers: Archaeological and Evolutionary Theory. Plenum Press, New York.

Bettinger, R L. 2016. Prehistoric Hunter–Gatherer Population Growth Rates Rival Those of Agriculturalists. Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA 113(4):812-814.

Childress, M.R. 2021. Summary and Discussion. In The SR 13 Flatwoods Bridge Project: Archaeological Testing and Data Recovery at the Elvis Riley Site (40PY288), Skelton Site (40PY289), and Thomason Site (40PY290), Perry County, Tennessee, by G.G. Weaver, J.W. Blazier, and A.R. Lunn, pp. 659-688. Weaver & Associates and Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Panamerican Report No. 40119. Submitted to the Tennessee Department of Transportation, Nashville.

Childress, M.R., and A. Saatkamp. 2021. Phase I Cultural Resources Survey of 372 Acres on the Kisatchie National Forest, Calcasieu Ranger District, Compartment 28, Rapides Parish, Louisiana. Panamerican Consultants, Memphis. Submitted to Kisatchie National Forest, Pineville, Louisiana.

Hassan, F. 1981. Demographic Archaeology. Academic Press, New York.

Pollack, D. (editor). 2008. The Archaeology of Kentucky: An Update. Kentucky Heritage Council, State Historic Preservation Comprehensive Plan No. 3. Lexington.

Zahid, H.J., E. Robinson, and R.L. Kelly. 2016. Agriculture, Population Growth, and Statistical Analysis of the Radiocarbon Record. Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA 113(4):931-935.

-

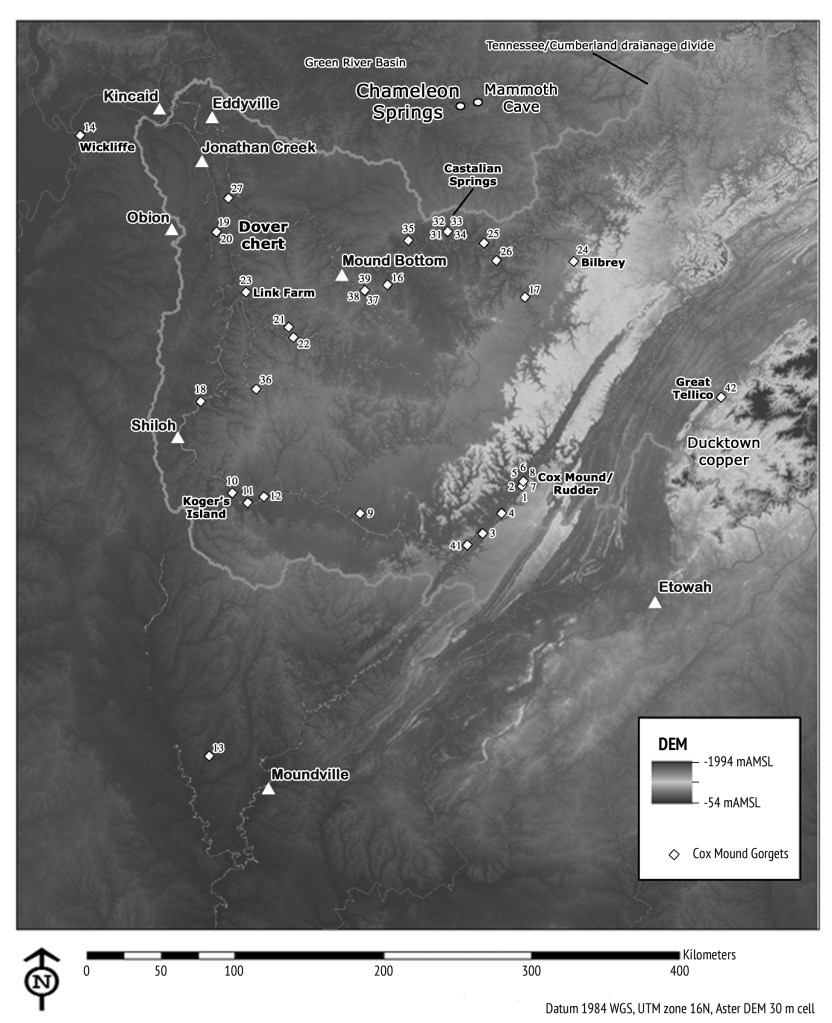

On the Provenance of the Thruston Mace

In looking briefly at an early draft of a recently published examination of the Braden style in the Middle Cumberland archaeological region (Sharp et al. 2020), I was struck by the illustration and brief discussion of the justly renowned Thruston mace (Figure 1), an item donated to Vanderbilt University along with a large regional collection of antiquities in 1907 (McGaw 1965; Weesner 1965). In his second edition of Antiquities of Tennessee, Thruston (1897:252b; Plate XIVB) stated that the artifact was “discovered some years ago in a grave in southern Kentucky, not far north of the Sumner County mound where the Myer gorget was found.” Thruston’s reference to the “Myer gorget” is, of course, to the masterful anthropomorphic Braden A/Eddyville marine shell specimen depicting a human figure in motion holding a near-replica of the Thruston mace in the left hand (Phillips and Brown 1978:180-182; Smith and Beahm 2010). The Braden A gorget was recovered ca. 1892 from the Mound 1 Grave 34 cedar log tomb burial at the Castalian Springs site, along with two fenestrated scalloped triskeles and two Cox Mound Pileated Woodpecker gorgets (see Figure 4). Given the remarkable similarity of the chipped stone mace to the engraved image of the hypertrophic weapon, it is understandable that Thruston would emphasize the general geographic proximity of the two artifacts. Based on Thruston’s statement, Robert Sharp and his colleagues speculated that the mace may have been recovered from a stone-box grave in Allen County, Kentucky. The Allen County region, just north of the Tennessee border, is dominated by several north-flowing tributaries of the Barren River, a stream that eventually debauches into the Green River at Woodbury, Kentucky near the Warren/Butler County line.

Figure 1. The Thruston Mace (photograph by David H. Dye, used with permission of the Tennessee State Museum, Gates P. Thruston collection of Vanderbilt University, 82.100.318). Within a few years of Thruston’s donation of his artifact collection, Colonel Bennett Young (1910) published an illustrated work on the antiquities of Kentucky. Young (1910:189-191) also briefly considered the chipped stone mace in the Thruston collection, and in his discussion of what he termed the “ceremonials of flint” provided the following:

The [ceremonial] flint objects . . . are among the most interesting of all chipped implements. It is likely that none of these were designed for practical use. We think the sickle-shaped, the scepters, and perhaps the other forms, had a ceremonial significance. These are from Trigg County, Kentucky, and Stewart, the adjoining county in Tennessee. General Gates P. Thruston, in his “Antiquities of Tennessee,” illustrates and describes many of these problematic objects of flint. The most remarkable is a scepter or mace of flint found in this State, and now in the collection of General Thruston. The illustration on page 189 is taken from his “Antiquities of Tennessee.” This wonderful object is fifteen and one fourth inches long and over five inches wide at the points. It is of dark gray chert. General Thruston writes: “I do not believe a finer or more elaborately wrought specimen of ancient chipped stone work than this old mace has ever been discovered.” Mr. R. B. Evans, of Glasgow, from whom this scepter was obtained by General Thruston, says it was found many years ago near Chameleon Springs, in Edmonson County, by a hunter who observed the end of it projecting from under a ledge of rock.

Obviously, the two roughly contemporaneous descriptions of the Thruston mace find-spot are at odds. It is rather remarkable that Young, while quoting from Thruston’s work, failed to point out the discrepancy. Perhaps he felt that providing such an incredibly specific account of the circumstances of recovery would ensure that his information on the mace would be determined the more reliable. Or perhaps it was simply the Colonel’s gentlemanly deference to the General. At any rate, the specificity of the Young provenience gives it much more salience than Thruston’s more generalized “mace obtained from an unspecified individual, from an unknown grave, from an unknown site in Kentucky, just north of Sumner County.” Nevertheless, Thruston’s vague provenance seems to have held sway for more than a century. It seems particularly significant that, according to Young’s account, the mace was not associated with a mortuary context as has long been assumed.

Chameleon Springs was a fairly well known natural mineral water spa and “long hunter” sporting resort that began as a seasonal camping site in 1804 (it doesn’t seem to show up on contemporary Google map searches). A hotel was eventually established there, and the lodgings were in active use until the 1930s. The locale is south of the Green River drainage, as can be seen on a portion of an archival map printed in Cram’s Ideal Reference Atlas from 1905 (see Figure 2 for approximate location). Another spring, Chalybeate (referring to iron-impregnated waters), is also shown on the atlas map just to the south and is prominent on the 1922 Mammoth Cave 1:62,500 scale (15-minute) and 1954 7.5-minute USGS maps of the area (Figure 3). A hotel was also established at Chalybeate that was in operation until World War II. The historic details about the Chameleon/Chalybeate Springs area correlate quite well with Young’s account of a hunter finding the Thruston mace on a rock ledge in that region. The local topography and drainage indicate that the mace may have been found somewhere along Beaverdam Creek or the adjacent ridges.

Figure 2. The interior Southeastern United States, showing the location of Chameleon Springs, Mammoth Cave, major late period prehistoric archaeological sites, exotic raw materials, and the distribution of Cox Mound gorgets (Brain and Phillips 1996; Buchner and Childress 1991; Childress 2015; Childress and Donohue 2015).

Figure 3. Principal geophysical landscapes in the Central Kentucky Karst region at Chameleon Springs (Chalybeate in small oval; base map, Mammoth Cave 1922 USGS 15-minute quadrangle) [Historical Topographic Map Collection] The Chameleon Springs vicinity falls squarely within one of the most celebrated karst regions in the world, and the primary entrances to Mammoth, Salts, and Crystal Caves are only a few kilometers to the east along the lower flanks of Flint and Mammoth Cave Ridges (Palmer 2016; Thornberry-Ehrlich 2011; Watson 1969). In addition to the ancient underground labyrinth, which has provided archaeological evidence for the most concentrated human use between about 4,000 and 2,000 years ago, the region abounds in sinking streams, springs, karst windows, and hidden sinkholes (witness the pock-marked Pennyroyal Plateau in Figure 3, a subdivision of the extensive sinkhole plain that extends into the eastern perimeter of the Nashville Basin). The abandonment or deliberate placement of the mace in this specific landscape (to suggest that such a remarkably rare and valuable power object was lost in the Chester Upland strains credulity) is thus a critical component of what has been provocatively referred to as “artifact biography” by Richard Bradley (2000), and considering its alternate provenance and career-ending stone-niche resting place expands our perspective on the interaction of portable votive offerings, mobility and boundary maintenance, prominent geographically fixed natural places, iconography, and, ultimately, aboriginal New World understandings of the organization of the cosmos. The mace is said to be crafted from a distinctive chert variety obtained from the Dover region in Stewart County, Tennessee, located some 160 km southwest of Chameleon Springs (Figure 2).

Kevin Smith (2013) has provided a relatively comprehensive assessment of the chronology and distribution of the mace as both artifact and image (see also Giles and Knapp 2015). Like Thruston before him, Smith seems to draw the closets possible parallels between the morphology of the Thruston mace and the image engraved on the Castalian Springs anthropomorphic gorget, and dates the marine shell specimen and the mace it depicts to the early classic Braden style horizon, ca. A.D. 1050–1150. The earliest depictions of the mace form are found on the rock walls of Picture Cave, Missouri, and have been dated through radiocarbon assay of pigments to ca. A.D. 950–1050 (Diaz-Granádos et al. 2001). These date ranges indicate that the chipped stone mace form necessarily pre-dates the earliest depictions of it, and the most ancient maces may thus be associated with the regional iconographic styles of the Late Woodland period in the American Bottom region prior to the emergence of Cahokia (see discussion of contemporaneous crested bird imagery from this region in Farnsworth and Koldehoff 2007). Curiously, Smith considers the Thruston mace to be a slightly later “hybrid” form dating to about A.D. 1200 (which he postulates as the terminal date for the production of chipped stone maces) rather than as a classic Braden-era form. The alternative find-spot at Chameleon Springs provides no new insight on the temporal placement of the Thruston mace, but its location outside the Cumberland Basin in a more northerly landscape emphasizes its stronger geographic association with the American Bottom region. The revised provenance for the Thruston mace strikingly parallels that of the long-nosed god mask now determined to have been recovered from a karst site near Rowena, Kentucky. Like the Thruston mace, this particular Late Woodland/Early Mississippian diagnostic was long assumed to have been recovered from a site along the Cumberland River very near Castalian Springs (Smith and Beahm 2009).

Ethnohistoric and archaeological evidence compiled by Dye (2014) on the regional prominence of imagery related to the “hero twins” takes on heightened significance considering the alternative provenance for the Thruston mace described by Bennett Young. As Dye emphasizes, the twins narrative and associated iconographic imagery are fundamental to the “basic Mississippian structural principle [of] the duality of essential complementary opposites.” The seemingly heterogeneous combination of thematic visual expressions in the Castalian Springs Grave 34 gorget assemblage may be “read” in a more comprehensive manner that incorporates this duality, with the nearly identical crested birds of the two Cox Mound gorgets revealing the twins in one of their other guises as the crested bird; twin triskeles elaborate the central element of the looped square. The special characteristics of a karst landscape are contrasted with the familiar “middle region” of typical diurnal activity: perpetual darkness/light; specially adapted cave creatures that have lost their pigmentation (white) living in total darkness (black). Duality is particularly well expressed in black (terrestrial slate) and white (marine shell) gorgets employing the same thematic expression, thus far only known for Cox Mound (twins; see Figure 4). Duality is also apparent in the nearly perfect bilateral symmetry of the chipped stone mace itself, and in other twin objects such as those in the Duck River cache from Link Farm (Peacock 1954; Figure 2). The absence of Cox Mound gorgets at contemporaneous sites with more apparent Cahokia affiliations presents another broad scale pattern of dual distribution. The mace, in both imaged and three-dimensional form, has a decided association with rock outcrops and karst features, perhaps reflecting the source of the flint from which it is chipped (see Hall 1983). A reconsideration of the Thruston mace find-spot may produce additional insights based on a more thorough review of contemporaneous sites in the Edmonson County portion of the Green River drainage (e.g., see papers in Carstens and Watson 1996).

Figure 4. Engraved Cox Mound gorget of black slate (diameter 7.1 cm), snapped diagonally across the corners of the looped square to create one of two “twin” pieces; recovered in an open setting near a permanent spring at the base of the Cumberland Plateau, Bilbrey site (No. 24, Figure 2; photograph by Candace Spearman). Acknowledgements. Drafts of this paper were read by David Dye, Jim Knight, Jack Rossen, Kevin Smith, and Larry Thomas, all of whom offered constructive criticism and helpful suggestions. Debbie Shaw at the Tennessee State Museum coordinated the Image Use Agreement required for Figure 1.

References Cited

Bradley, R. 2000. An Archaeology of Natural Places. Routledge, London.

Brain, J.P., and P. Phillips. 1996. Shell Gorgets: Styles of the Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Southeast. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Buchner, C.A., and M.R. Childress. 1991. A Southeastern Ceremonial Complex Gorget from Putnam County, Tennessee. Tennessee Anthropological Association Newsletter 16(6):1-4.

Carstens, K.C., and P.J. Watson (editors). 1996. Of Caves and Shell Mounds. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Childress, M.R. 2015. Cox Mound Gorgets: Distributions, Chronology, and Style. FABBL Presentation, Department of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Childress, M.R., and L. Donohue. 2015. A GIS Approach to the Spatial Distribution of Cox Mound Gorgets. Poster presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Nashville, Tennessee.

Diaz-Granádos, C., M.W. Rowe, M. Hyman, J.R. Duncan, and J.R. Southon. 2001. AMS Radiocarbon Dates for Charcoal from Three Missouri Pictographs and Their Associated Iconography. American Antiquity 66(3):481-492.

Dye, D.H. 2014. Lightning Boy Face Mask Gorgets and Thunder Boy War Clubs: The Ritual Organization of the Lower Mississippi Valley. Paper presented at the 71st Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Greenville, South Carolina.

Farnsworth, K.B., and B. Koldehoff. 2007. Kingfisher-Effigy Bone Hairpins: Late Woodland Iconography and Social Complexity in West-Central Illinois. Illinois Archaeology 15 & 16:30-57.

Giles, B.T., and T.D. Knapp. 2015. A Mississippian Mace at Iroquoia’s Southern Door. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 40(1):73-95.

Hall, R.L. 1983. A Pan-continental Perspective on Red Ocher and Glacial Kame Ceremonialism. In Lulu Linear Punctated: Essays in Honor of George Irving Quimby, edited by R.C. Dunnell and D.K. Grayson, pp. 74-107. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 72. Ann Arbor.

McGaw, R.A. 1965. Tennessee Antiquities Re-Exhumed: The New Exhibit of the Thruston Collection at Vanderbilt, Part I. Tennessee Historical Quarterly XXIV(2):121-135.

Palmer, A.N. 2016. The Mammoth Cave System, Kentucky, USA. Boletín Geológico y Minero 127(1):131-145.

Peacock, C.K. 1954. Duck River Cache: Tennessee’s Greatest Archaeological Find. Tennessee Archaeological Society, Chattanooga. (Reprinted ca. 1984, with a preface by Q.R. Bass, Mini-Histories, Nashville).

Phillips, P., and J.A. Brown. 1978. Pre-Columbian Shell Engravings from the Craig Mound at Spiro, Oklahoma. Part 1. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sharp, R.V., K.E. Smith, and D.H. Dye. 2020. Cahokians and the Circulation of Ritual Goods in the Middle Cumberland Region. In Cahokia in Context: Hegemony and Diaspora, edited by C.H. McNutt and R.M. Parish, pp. 319-351. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Smith, K.E. 2013. The Mace Motif in Mississippian Iconography (AD 1000–1500). Paper presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Tampa, Florida.

Smith, K.E., and E. Beahm. 2009. Corrected Provenance for the Long-Nosed God Mask from “A Cave near Rogana, Tennessee.” Southeastern Archaeology 28(1):117-121.

Smith, K.E., and E. Beahm. 2010. Reconciling the Puzzle of Castalian Springs Grave 34: Scalloped Triskeles, Crested Birds, and the Braden A/Eddyville Gorget. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, St. Louis.

Thornberry-Ehrlich, T. 2011. Mammoth Cave National Park: Geologic Resources Inventory Report. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2011/448. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Thruston, G.P. 1897. The Antiquities of Tennessee and the Adjacent States (second edition). Robert Clarke, Cincinnati.

Watson, P.J. 1969. The Prehistory of Salts Cave, Kentucky. Illinois State Museum Reports of Investigations 16.

Weesner, R.W. 1965. Tennessee Antiquities Re-Exhumed, Part II. Tennessee Historical Quarterly XXIV(2):136-142.

Young, B.H. 1910. The Prehistoric Men of Kentucky. John P. Morton & Company, Louisville, Kentucky (printed for the Filson Club, Publication No. 25). Public domain University of Michigan digitized pdf. http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd.

-

Blakemore

Blakemore Mounds is a recently documented prehistoric earthwork complex on the right bank of the Middle Fork Forked Deer River near Humboldt, Gibson County, Tennessee. It is located at the physiographic interface of the loess sheet of the Western Plains and the upland Coastal Plains sands and clays. The archaeological site, whose Smithsonian trinomial is 40GB206, was identified based on recognition of a small cemetery on the surface of a low rectangular platform mound. The summit graves date from ca. 1850 to 1935 and are associated with the Blakemore and Crafton families, who settled in this part of West Tennessee shortly after the Chickasaw Purchase around 1825.

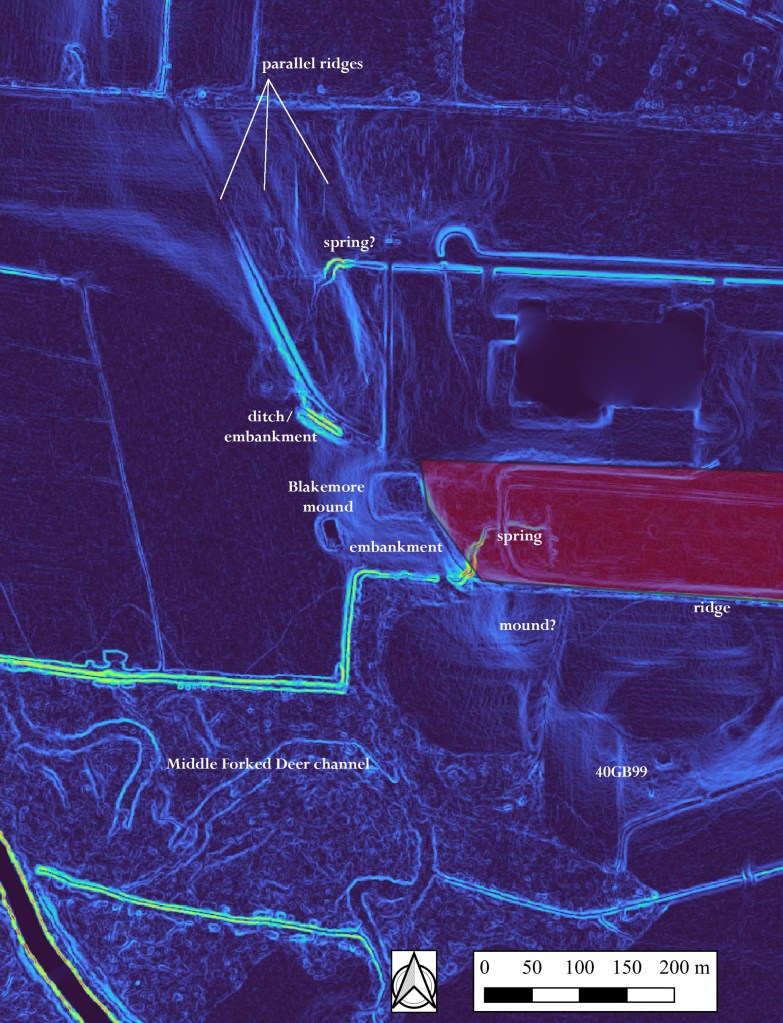

Figure 1. False color LiDAR image of Blakemore landscape features (surveyed area in red;

base:NRCS 2011 tif x32y397).Spoil dirt from a shallow animal burrow located on the southwestern summit of the platform mound yielded numerous diagnostic prehistoric ceramics, including Late Archaic baked clay object fragments and Early Woodland pottery vessel sherds typed as Mulberry Creek Cordmarked, var. Tishomingo and Withers Fabric Marked, var. Craig’s Landing. The documented earthworks thus far consist of a low rectangular platform mound, a connected linear embankment breached by a spring-fed tributary, a deep ditch/embankment complex, barrow areas, and flanking parallel ridges. The larger landscape, encompassing approximately 144 ha, is a roughly rectangular elevated terrace of more resistant ferruginous sandstone capped with loess surrounded on three sides by tributaries. An eroded ring of Grenada silt loam defines the landscape perimeter. Although no radiocarbon dates are available, the site is thought to have been constructed and used ca. 300 BC–AD 100.

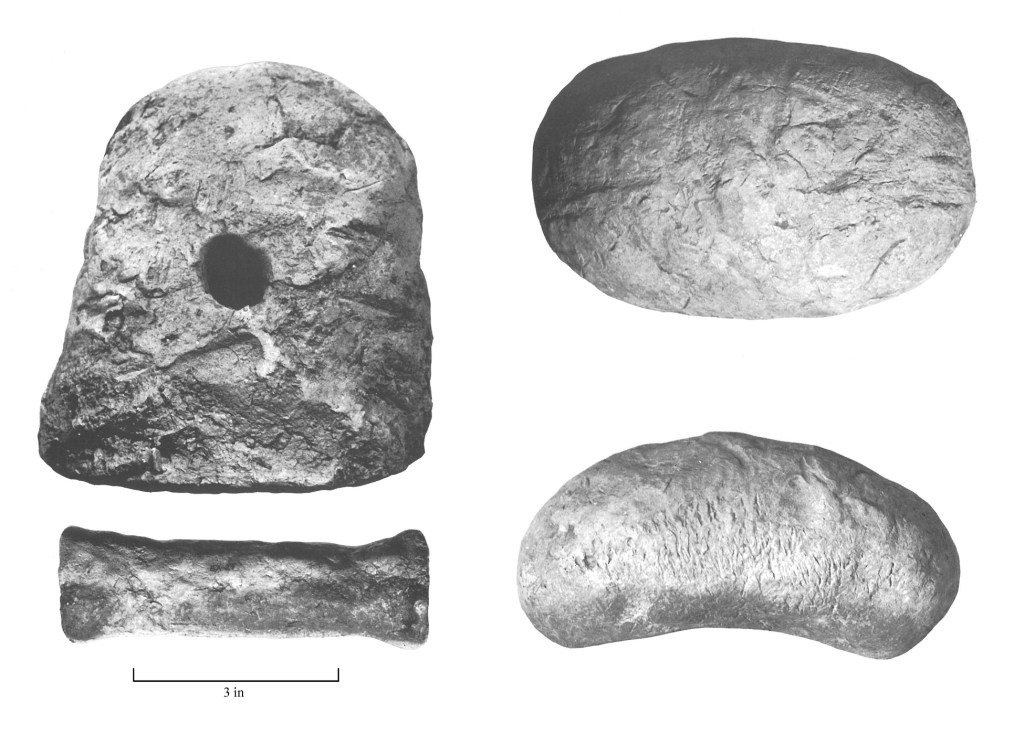

Figure 2. Artifacts from the Blakemore Mound surface artifact concentration; a: ferruginous sandstone tool fragments; b: chert flakes; c: quartzite fragment; d: ceramic sherds.

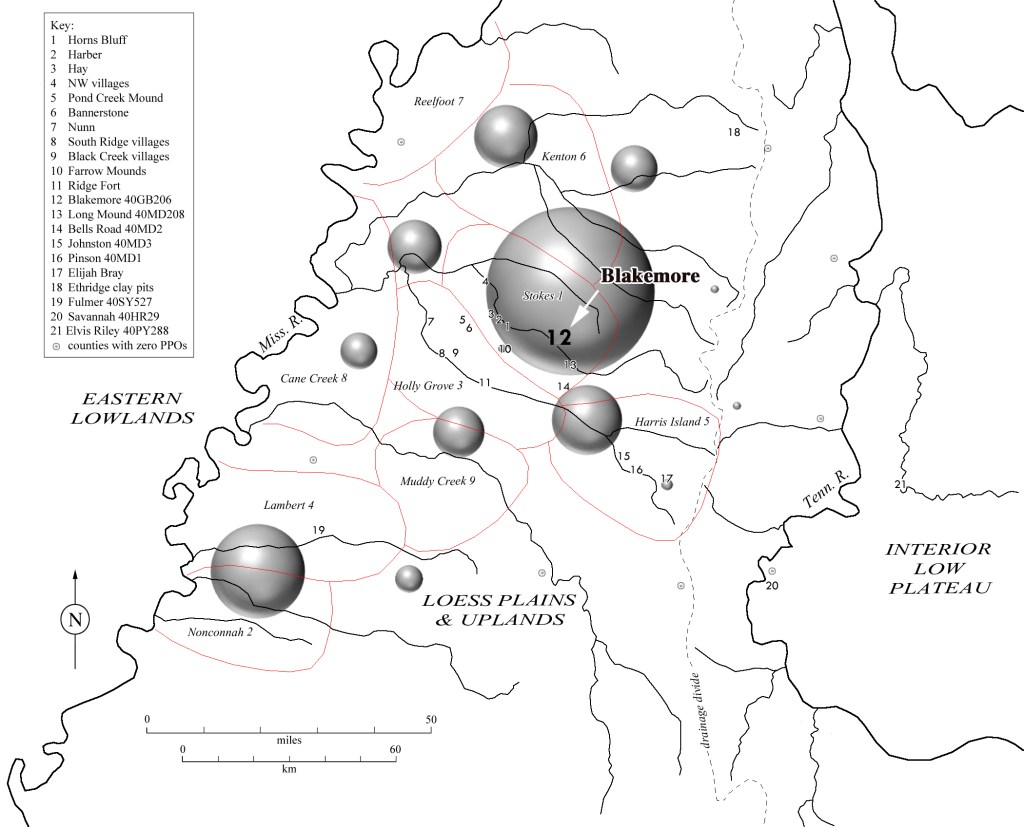

Figure 3. Artifacts from the Blakemore Mound surface artifact concentration; a: ceramic sherds; b: Poverty Point object fragments; c: heat treated chert thinning flake; d: ferruginous sandstone fragments. The Blakemore landscape is near the center of the largest concentration of Poverty Point era (ca. 1600-1000 BC) diagnostics in this portion of the central Mississippi River Valley and may have functioned as the predominant ceremonial site for local populations during the Terminal Archaic-Early Woodland interval. Several roughly coeval sites were documented in adjacent Crockett County during the antiquarian era. Details of the landscape features at the site, including connected ridges and platform mounds oriented at roughly 330⁰ and associated springs proximal to breaks in the embankment lines, have direct parallels to those found at Johnston Mounds (40MD3) in the upper South Fork Forked Deer drainage of Madison County, Tennessee.

Figure 4. West Tennessee regional Late Archaic–Middle Woodland archaeological distributions (gray bubbles are Poverty Point Object quantities by county). For more technical details and related references see the post on my page at academia.edu: Blakemore Mounds (40GB206) and the Terminal Archaic–Middle Woodland Archaeological Record in West Tennessee

Mitchell R. Childress, September 2, 2022

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.