In looking briefly at an early draft of a recently published examination of the Braden style in the Middle Cumberland archaeological region (Sharp et al. 2020), I was struck by the illustration and brief discussion of the justly renowned Thruston mace (Figure 1), an item donated to Vanderbilt University along with a large regional collection of antiquities in 1907 (McGaw 1965; Weesner 1965). In his second edition of Antiquities of Tennessee, Thruston (1897:252b; Plate XIVB) stated that the artifact was “discovered some years ago in a grave in southern Kentucky, not far north of the Sumner County mound where the Myer gorget was found.” Thruston’s reference to the “Myer gorget” is, of course, to the masterful anthropomorphic Braden A/Eddyville marine shell specimen depicting a human figure in motion holding a near-replica of the Thruston mace in the left hand (Phillips and Brown 1978:180-182; Smith and Beahm 2010). The Braden A gorget was recovered ca. 1892 from the Mound 1 Grave 34 cedar log tomb burial at the Castalian Springs site, along with two fenestrated scalloped triskeles and two Cox Mound Pileated Woodpecker gorgets (see Figure 4). Given the remarkable similarity of the chipped stone mace to the engraved image of the hypertrophic weapon, it is understandable that Thruston would emphasize the general geographic proximity of the two artifacts. Based on Thruston’s statement, Robert Sharp and his colleagues speculated that the mace may have been recovered from a stone-box grave in Allen County, Kentucky. The Allen County region, just north of the Tennessee border, is dominated by several north-flowing tributaries of the Barren River, a stream that eventually debauches into the Green River at Woodbury, Kentucky near the Warren/Butler County line.

Within a few years of Thruston’s donation of his artifact collection, Colonel Bennett Young (1910) published an illustrated work on the antiquities of Kentucky. Young (1910:189-191) also briefly considered the chipped stone mace in the Thruston collection, and in his discussion of what he termed the “ceremonials of flint” provided the following:

The [ceremonial] flint objects . . . are among the most interesting of all chipped implements. It is likely that none of these were designed for practical use. We think the sickle-shaped, the scepters, and perhaps the other forms, had a ceremonial significance. These are from Trigg County, Kentucky, and Stewart, the adjoining county in Tennessee. General Gates P. Thruston, in his “Antiquities of Tennessee,” illustrates and describes many of these problematic objects of flint. The most remarkable is a scepter or mace of flint found in this State, and now in the collection of General Thruston. The illustration on page 189 is taken from his “Antiquities of Tennessee.” This wonderful object is fifteen and one fourth inches long and over five inches wide at the points. It is of dark gray chert. General Thruston writes: “I do not believe a finer or more elaborately wrought specimen of ancient chipped stone work than this old mace has ever been discovered.” Mr. R. B. Evans, of Glasgow, from whom this scepter was obtained by General Thruston, says it was found many years ago near Chameleon Springs, in Edmonson County, by a hunter who observed the end of it projecting from under a ledge of rock.

Obviously, the two roughly contemporaneous descriptions of the Thruston mace find-spot are at odds. It is rather remarkable that Young, while quoting from Thruston’s work, failed to point out the discrepancy. Perhaps he felt that providing such an incredibly specific account of the circumstances of recovery would ensure that his information on the mace would be determined the more reliable. Or perhaps it was simply the Colonel’s gentlemanly deference to the General. At any rate, the specificity of the Young provenience gives it much more salience than Thruston’s more generalized “mace obtained from an unspecified individual, from an unknown grave, from an unknown site in Kentucky, just north of Sumner County.” Nevertheless, Thruston’s vague provenance seems to have held sway for more than a century. It seems particularly significant that, according to Young’s account, the mace was not associated with a mortuary context as has long been assumed.

Chameleon Springs was a fairly well known natural mineral water spa and “long hunter” sporting resort that began as a seasonal camping site in 1804 (it doesn’t seem to show up on contemporary Google map searches). A hotel was eventually established there, and the lodgings were in active use until the 1930s. The locale is south of the Green River drainage, as can be seen on a portion of an archival map printed in Cram’s Ideal Reference Atlas from 1905 (see Figure 2 for approximate location). Another spring, Chalybeate (referring to iron-impregnated waters), is also shown on the atlas map just to the south and is prominent on the 1922 Mammoth Cave 1:62,500 scale (15-minute) and 1954 7.5-minute USGS maps of the area (Figure 3). A hotel was also established at Chalybeate that was in operation until World War II. The historic details about the Chameleon/Chalybeate Springs area correlate quite well with Young’s account of a hunter finding the Thruston mace on a rock ledge in that region. The local topography and drainage indicate that the mace may have been found somewhere along Beaverdam Creek or the adjacent ridges.

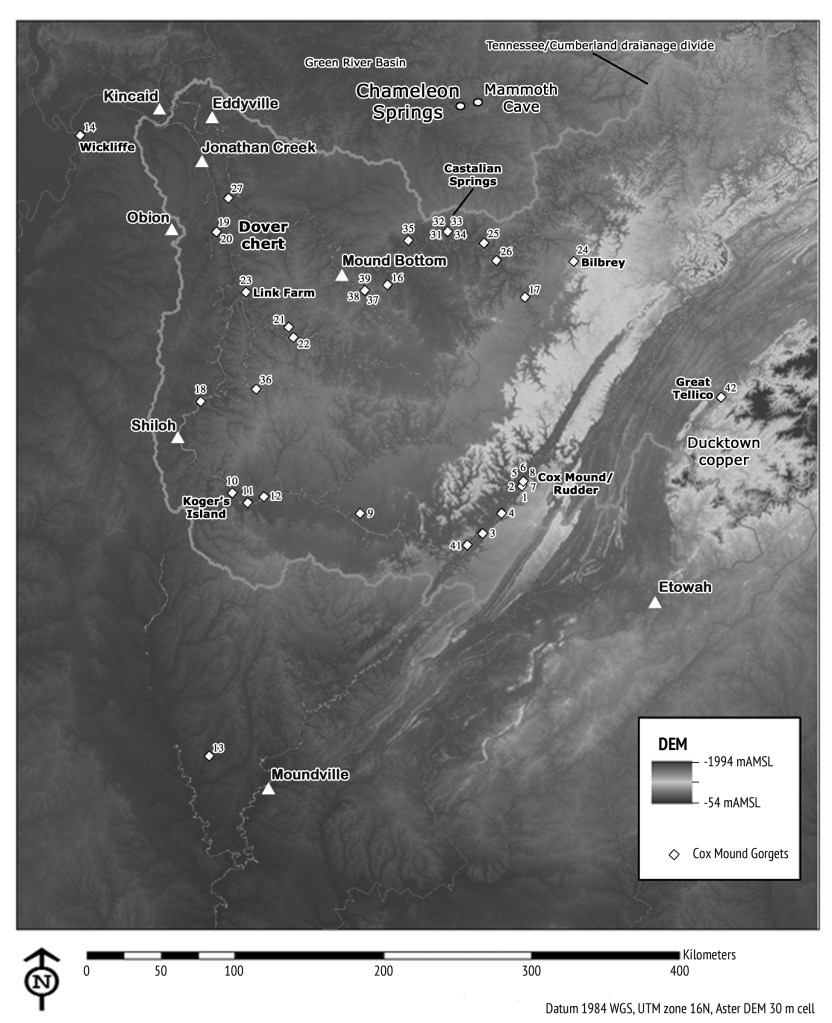

The Chameleon Springs vicinity falls squarely within one of the most celebrated karst regions in the world, and the primary entrances to Mammoth, Salts, and Crystal Caves are only a few kilometers to the east along the lower flanks of Flint and Mammoth Cave Ridges (Palmer 2016; Thornberry-Ehrlich 2011; Watson 1969). In addition to the ancient underground labyrinth, which has provided archaeological evidence for the most concentrated human use between about 4,000 and 2,000 years ago, the region abounds in sinking streams, springs, karst windows, and hidden sinkholes (witness the pock-marked Pennyroyal Plateau in Figure 3, a subdivision of the extensive sinkhole plain that extends into the eastern perimeter of the Nashville Basin). The abandonment or deliberate placement of the mace in this specific landscape (to suggest that such a remarkably rare and valuable power object was lost in the Chester Upland strains credulity) is thus a critical component of what has been provocatively referred to as “artifact biography” by Richard Bradley (2000), and considering its alternate provenance and career-ending stone-niche resting place expands our perspective on the interaction of portable votive offerings, mobility and boundary maintenance, prominent geographically fixed natural places, iconography, and, ultimately, aboriginal New World understandings of the organization of the cosmos. The mace is said to be crafted from a distinctive chert variety obtained from the Dover region in Stewart County, Tennessee, located some 160 km southwest of Chameleon Springs (Figure 2).

Kevin Smith (2013) has provided a relatively comprehensive assessment of the chronology and distribution of the mace as both artifact and image (see also Giles and Knapp 2015). Like Thruston before him, Smith seems to draw the closets possible parallels between the morphology of the Thruston mace and the image engraved on the Castalian Springs anthropomorphic gorget, and dates the marine shell specimen and the mace it depicts to the early classic Braden style horizon, ca. A.D. 1050–1150. The earliest depictions of the mace form are found on the rock walls of Picture Cave, Missouri, and have been dated through radiocarbon assay of pigments to ca. A.D. 950–1050 (Diaz-Granádos et al. 2001). These date ranges indicate that the chipped stone mace form necessarily pre-dates the earliest depictions of it, and the most ancient maces may thus be associated with the regional iconographic styles of the Late Woodland period in the American Bottom region prior to the emergence of Cahokia (see discussion of contemporaneous crested bird imagery from this region in Farnsworth and Koldehoff 2007). Curiously, Smith considers the Thruston mace to be a slightly later “hybrid” form dating to about A.D. 1200 (which he postulates as the terminal date for the production of chipped stone maces) rather than as a classic Braden-era form. The alternative find-spot at Chameleon Springs provides no new insight on the temporal placement of the Thruston mace, but its location outside the Cumberland Basin in a more northerly landscape emphasizes its stronger geographic association with the American Bottom region. The revised provenance for the Thruston mace strikingly parallels that of the long-nosed god mask now determined to have been recovered from a karst site near Rowena, Kentucky. Like the Thruston mace, this particular Late Woodland/Early Mississippian diagnostic was long assumed to have been recovered from a site along the Cumberland River very near Castalian Springs (Smith and Beahm 2009).

Ethnohistoric and archaeological evidence compiled by Dye (2014) on the regional prominence of imagery related to the “hero twins” takes on heightened significance considering the alternative provenance for the Thruston mace described by Bennett Young. As Dye emphasizes, the twins narrative and associated iconographic imagery are fundamental to the “basic Mississippian structural principle [of] the duality of essential complementary opposites.” The seemingly heterogeneous combination of thematic visual expressions in the Castalian Springs Grave 34 gorget assemblage may be “read” in a more comprehensive manner that incorporates this duality, with the nearly identical crested birds of the two Cox Mound gorgets revealing the twins in one of their other guises as the crested bird; twin triskeles elaborate the central element of the looped square. The special characteristics of a karst landscape are contrasted with the familiar “middle region” of typical diurnal activity: perpetual darkness/light; specially adapted cave creatures that have lost their pigmentation (white) living in total darkness (black). Duality is particularly well expressed in black (terrestrial slate) and white (marine shell) gorgets employing the same thematic expression, thus far only known for Cox Mound (twins; see Figure 4). Duality is also apparent in the nearly perfect bilateral symmetry of the chipped stone mace itself, and in other twin objects such as those in the Duck River cache from Link Farm (Peacock 1954; Figure 2). The absence of Cox Mound gorgets at contemporaneous sites with more apparent Cahokia affiliations presents another broad scale pattern of dual distribution. The mace, in both imaged and three-dimensional form, has a decided association with rock outcrops and karst features, perhaps reflecting the source of the flint from which it is chipped (see Hall 1983). A reconsideration of the Thruston mace find-spot may produce additional insights based on a more thorough review of contemporaneous sites in the Edmonson County portion of the Green River drainage (e.g., see papers in Carstens and Watson 1996).

Acknowledgements. Drafts of this paper were read by David Dye, Jim Knight, Jack Rossen, Kevin Smith, and Larry Thomas, all of whom offered constructive criticism and helpful suggestions. Debbie Shaw at the Tennessee State Museum coordinated the Image Use Agreement required for Figure 1.

References Cited

Bradley, R. 2000. An Archaeology of Natural Places. Routledge, London.

Brain, J.P., and P. Phillips. 1996. Shell Gorgets: Styles of the Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Southeast. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Buchner, C.A., and M.R. Childress. 1991. A Southeastern Ceremonial Complex Gorget from Putnam County, Tennessee. Tennessee Anthropological Association Newsletter 16(6):1-4.

Carstens, K.C., and P.J. Watson (editors). 1996. Of Caves and Shell Mounds. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Childress, M.R. 2015. Cox Mound Gorgets: Distributions, Chronology, and Style. FABBL Presentation, Department of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Childress, M.R., and L. Donohue. 2015. A GIS Approach to the Spatial Distribution of Cox Mound Gorgets. Poster presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Nashville, Tennessee.

Diaz-Granádos, C., M.W. Rowe, M. Hyman, J.R. Duncan, and J.R. Southon. 2001. AMS Radiocarbon Dates for Charcoal from Three Missouri Pictographs and Their Associated Iconography. American Antiquity 66(3):481-492.

Dye, D.H. 2014. Lightning Boy Face Mask Gorgets and Thunder Boy War Clubs: The Ritual Organization of the Lower Mississippi Valley. Paper presented at the 71st Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Greenville, South Carolina.

Farnsworth, K.B., and B. Koldehoff. 2007. Kingfisher-Effigy Bone Hairpins: Late Woodland Iconography and Social Complexity in West-Central Illinois. Illinois Archaeology 15 & 16:30-57.

Giles, B.T., and T.D. Knapp. 2015. A Mississippian Mace at Iroquoia’s Southern Door. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 40(1):73-95.

Hall, R.L. 1983. A Pan-continental Perspective on Red Ocher and Glacial Kame Ceremonialism. In Lulu Linear Punctated: Essays in Honor of George Irving Quimby, edited by R.C. Dunnell and D.K. Grayson, pp. 74-107. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 72. Ann Arbor.

McGaw, R.A. 1965. Tennessee Antiquities Re-Exhumed: The New Exhibit of the Thruston Collection at Vanderbilt, Part I. Tennessee Historical Quarterly XXIV(2):121-135.

Palmer, A.N. 2016. The Mammoth Cave System, Kentucky, USA. Boletín Geológico y Minero 127(1):131-145.

Peacock, C.K. 1954. Duck River Cache: Tennessee’s Greatest Archaeological Find. Tennessee Archaeological Society, Chattanooga. (Reprinted ca. 1984, with a preface by Q.R. Bass, Mini-Histories, Nashville).

Phillips, P., and J.A. Brown. 1978. Pre-Columbian Shell Engravings from the Craig Mound at Spiro, Oklahoma. Part 1. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sharp, R.V., K.E. Smith, and D.H. Dye. 2020. Cahokians and the Circulation of Ritual Goods in the Middle Cumberland Region. In Cahokia in Context: Hegemony and Diaspora, edited by C.H. McNutt and R.M. Parish, pp. 319-351. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Smith, K.E. 2013. The Mace Motif in Mississippian Iconography (AD 1000–1500). Paper presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Tampa, Florida.

Smith, K.E., and E. Beahm. 2009. Corrected Provenance for the Long-Nosed God Mask from “A Cave near Rogana, Tennessee.” Southeastern Archaeology 28(1):117-121.

Smith, K.E., and E. Beahm. 2010. Reconciling the Puzzle of Castalian Springs Grave 34: Scalloped Triskeles, Crested Birds, and the Braden A/Eddyville Gorget. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, St. Louis.

Thornberry-Ehrlich, T. 2011. Mammoth Cave National Park: Geologic Resources Inventory Report. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2011/448. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Thruston, G.P. 1897. The Antiquities of Tennessee and the Adjacent States (second edition). Robert Clarke, Cincinnati.

Watson, P.J. 1969. The Prehistory of Salts Cave, Kentucky. Illinois State Museum Reports of Investigations 16.

Weesner, R.W. 1965. Tennessee Antiquities Re-Exhumed, Part II. Tennessee Historical Quarterly XXIV(2):136-142.

Young, B.H. 1910. The Prehistoric Men of Kentucky. John P. Morton & Company, Louisville, Kentucky (printed for the Filson Club, Publication No. 25). Public domain University of Michigan digitized pdf. http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd.