Abstract. Recent work at two archaeological sites, Ohlendorf (3MS796) and Edmondson Farmstead (3CT73), in the lowlands of eastern Arkansas have produced artifacts and faunal remains that are associated with the production of textiles. Unusual baked clay artifacts that appear to be loom weights have been recovered along with ceramic disc spindle whorls from several sites in the region. The recovery of the nearly complete skeleton of a mature opossum, combined with ethnographic descriptions of the production of opossum fur fibers, suggests these animals may have been kept as raw material sources.

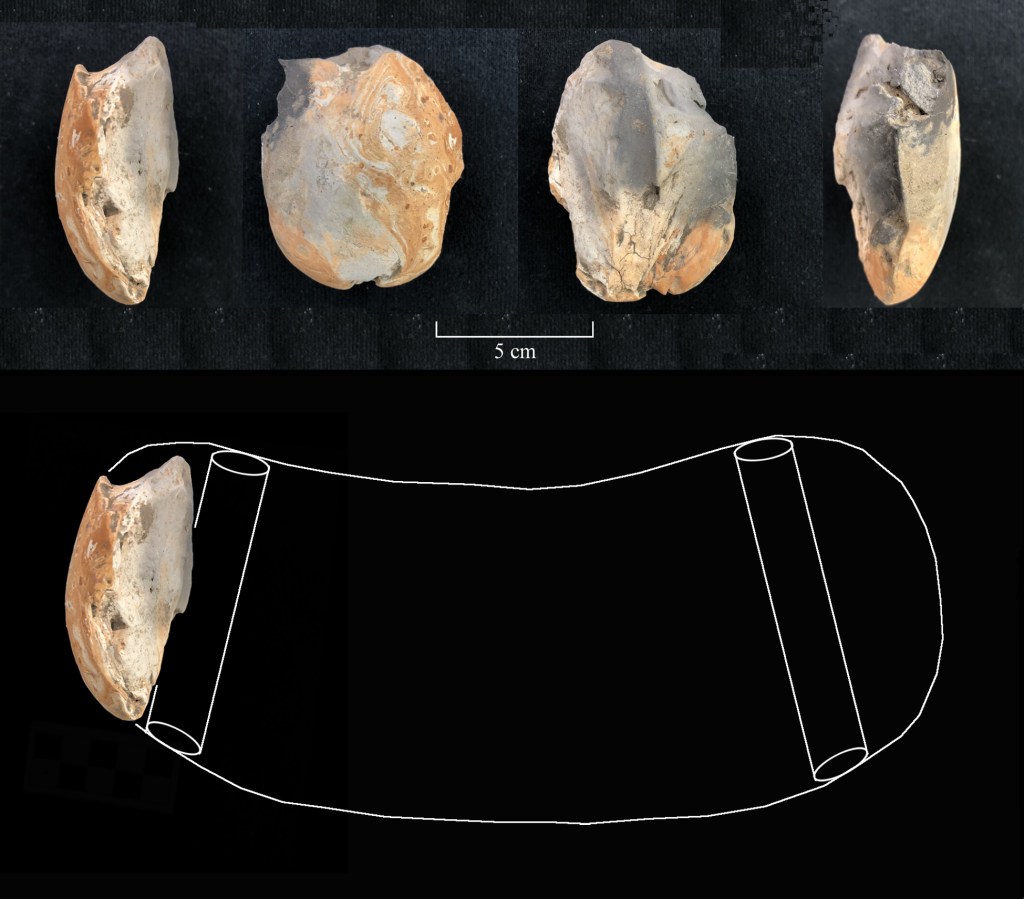

From a controlled surface collection of artifacts obtained from the ca. AD 1300-1600 Ohlendorf site (Buchner et al. 2022), an unusual artifact fragment was recovered (Figure 1). It is made of varicolored clay and seems to be constructed of two layers: an inner massive core which is fairly homogeneous in structure and an outer thinly laminated swirled coating that is about 4–5 mm thick. The clay has a raspy texture and is tempered with very fine sand throughout. The inner core is gray and white, while the thinner outer coating is mostly pale gray and orange. On the interior of the object is approximately 20 percent of a perfectly cylindrical channel or hole that would have had a diameter of about 1.7 mm. There are no impressions on the channel, suggesting that the clay was formed around a very smooth object such as a joint of river cane. The artifact has a volume of about 26.5 cm3 and a mass of 81.5 g. It is thought to be the end of a large, symmetrical loaf-shaped fired clay artifact with two perforations as shown in the lower panel of Figure 1. Another part of the same object (non-conjoinable) and two other even more fragmentary coarse shell tempered specimens with similar channels were recovered from the Ohlendorf site surface.

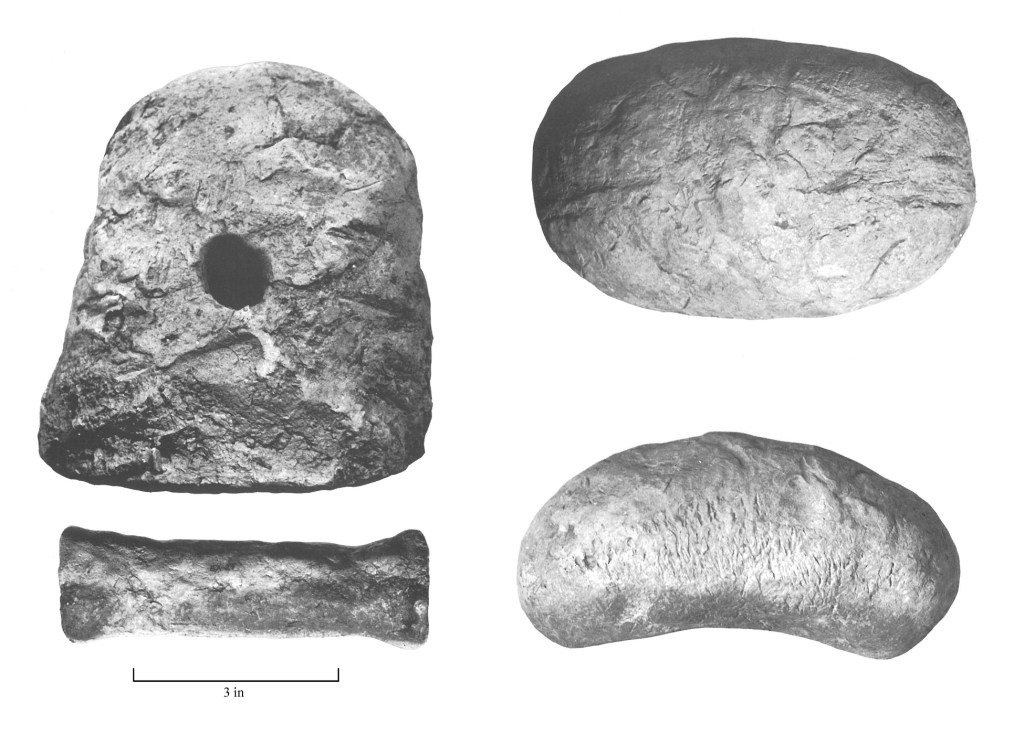

The hypothesized reconstruction of the complete artifact from the Ohlendorf fragment is based on an item of apparently identical form originally brought to my attention in the spring of 1993 (Figure 2). The fired clay object has a volume of about 930 cm3 and a mass of 2850 g. It was then among a collection of prehistoric site materials assembled by a Dr. Daniel A. Buechner, III of Memphis, Tennessee. The site, labeled by Dr. Buechner as “A3,” was not located on a map, but other material from the surface collection included two large rim sherds of Barton Incised, var. Togo, six rims of Barton Incised, var. Barton, four pieces of Mississippi Plain, var. Neeley’s Ferry (1 bowl rim, 1 bottle neck, 2 jar lugs), three sherds of Parkin Punctated, one sherd of Walls Engraved, one sherd of Old Town Red, and a large fragment of cane-impressed daub. Identified sites from which other materials had been obtained were Rose Mound and Parkin on the Lower St. Francis; Walls, Lake Cormorant, Irby, and Withers south of Horn Lake in northwest Mississippi; and Mound Place in eastern Crittenden County, Arkansas. Based on the diagnostic ceramics, the geographic range of the identified sites, and the occurrence of similar loaf-shaped artifacts, we feel confident that the Buechner “A3” collection is probably from a Late Mississippian site (ca. AD 1000-1550) in the Walls, Horseshoe Lake, or southern Nodena phase areas.

An object almost identical to the Buechner specimen was excavated in 1957 by Gregory Perino (1966) at the Banks Village site (Figure 3, right panel). The Banks Village artifact, which Perino considered to be of “doubtful utility” but speculated may have been a “pottery support,” lacks perforations but does have portions of a cord groove on the convex surface parallel to the long axis (cf. Figure 2, top). Both items also had remnant fabric markings on the exterior. Another perforated clay object and a flare-ended clay bar (Figure 3, left) were recovered within one of the houses. The Banks Village site also yielded several spool-shaped clay artifacts for which no function was hypothesized.

The Lawhorn site (3CG1), located about 50 km northwest of Ohlendorf on the St. Francis River, also yielded several similar fired clay objects, one of which contained a large central perforation that Moselage (1962:61; Figure 27-1) speculated may have functioned as a loom weight. Another unillustrated fired clay specimen is described as containing a groove around a portion of the margin and another with “a coarse textile impression on one side and a surface well smoothed on the other.” These details both occur on the complete perforated object from Dr. Buechner’s site A3 (Figure 2). In addition to the possible loom weight fragments, the Lawhorn site yielded 27 perforated sherd disc spindle whorls that ranged in size from 3 to 8 cm in diameter, attesting to the importance of fiber production at the site. The spindle whorls were mainly associated with the excavated house floors (Moselage 1962:44; 69-80; see Alt 1999 for detailed discussion of Mississippian spindle whorls and fiber production). The Ohlendorf controlled surface collection contained only two unperforated ceramic sherd discs, but extensive archaeological research at the site would doubtlessly provide additional evidence of fiber production and textile manufacture.

In agreement with Moselage, we consider all the unusual baked clay objects recovered from Ohlendorf, Banks Village, and Lawhorn to be loom weights. They match the descriptions and morphology of Old-World examples remarkably well (see Gleba and Cutler 2012; Mårtensson et al. 2009), but appear to have been too massive and bulky for use on groups of warp threads as would have been employed on a hanging warp-weighted loom (see Lipo et al. 2011:Figure 8). The range of spindle whorl sizes recorded at late period sites in the region suggest quite a range of thread sizes from fine to rather coarse (the Ohlendorf sherd discs had weights of 13.2 g and 31.5 g, which would have produced thick yarn threads in the 4–9 mm size range if used as spindle whorls). If these large, fired clay objects are loom weights, they were probably hung from a lower bar on which the bottoms of the individual warp threads were attached. More insight could be provided through replication study.

An unusual opossum burial from the contemporaneous Edmondson Farmstead site (3CT73; Childress et al. 2022) provides additional indirect evidence for the importance of fiber and textile work in the region. The intentionally interred skeleton was nearly complete and tooth wear indicated that the animal was quite old; these unusual marsupials have a very short life span and rarely survive for more than about two years in the wild. While they are certainly documented as food sources their frequencies in faunal collections are usually below what would be a expected given their population density and ease of capture. Swanton (1946) provides several ethnographic examples of the use of opossum fur for the production of fibers and textiles, and the 3CT73 specimen indicates that the animals may have been kept in village areas as a ready source of fur.

References Cited

Alt, S., 1999. Spindle Whorls and Fiber Production at Early Cahokian Settlements. Southeastern Archaeology 18(2):124–134.

Buchner, C.A., M.R. Childress, J. Rossen, and A. Baer. 2022. Phase I Cultural Resources Survey of the 2401.79-Acre Exploratory Ventures LLC Proposed Project in Mississippi County, Arkansas. Commonwealth Heritage Group/Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Childress, M.R., J. Rossen, C.A. Buchner, and A. Baer. 2022. Archaeology at Edmondson Farmstead (3CT73), Crittenden County, Arkansas. Commonwealth Heritage Group/Panamerican Consultants, Memphis, Tennessee. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Memphis District.

Gleba, M., and J. Cutler. 2012. Textile Production in Bronze Age Miletos: First Observations. In Kosmos: Jewellery, Adornment, and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age, edited by Marie-Louise Nosch and Robert Laffineur, pp. 113–121. Peeters Leuven, Liege.

Lipo, C.P., T.D. Hunt, and R.C. Dunnell. 2011. Formal Analyses and Functional Accounts of Groundstone “Plummets” from Poverty Point, Louisiana. Journal of Archaeological Science, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.004.

Mårtensson, L., M. Nosch, and E.A. Strand. 2009. Shape of Things: Understanding a Loom Weight. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 28(4):373–398.

Morse, D.F. (editor). 1989. Nodena: An Account of 90 Years of Archaeological Investigation in Southeast Mississippi County, Arkansas. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 30 (second edition).

Moselage, J. 1962. The Lawhorn Site. The Missouri Archaeologist 24:1–110.

Perino, G. 1966. The Banks Village Site, Crittenden County, Arkansas. Missouri Archaeological Society Memoir No. 4, Columbia.

Swanton, J.R. 1946. The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 137. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Williams, J. R. 1974. The Baytown Phases in the Cairo Lowland of Southeast Missouri. The Missouri Archaeologist 36:1–109.