To understand the past, we must understand places. — Lewis R. Binford

The late archaeologist Lewis Binford (1931–2011) pioneered the application of ethnographic observation to the construction of archaeological theory, particularly as it applied to that long span of time during which the pre-agricultural or hunting-and-gathering adaptation was exclusively operative. In a series of highly influential writings published in the early 1980s (e.g., Binford 1980, 1982, 1983) he provided perspectives on the relationship between the distribution of complex living systems and their material correlates in space that challenged what he referred to as the traditional “normative view” of Old and New World cultural historians. Binford suggested that patterns registered in the archaeological record, particularly those at deep stratified sites with very long sequences, could not be reliably “read” without a more complete understanding of the effects of mobility and long-term land use patterns on the changing use of the same places in a landscape. Later in time, with increasing population density and reduced mobility,

We may anticipate increasing repetition in the use of particular places . . . It should be clear that when residential mobility is at a minimum the economic potential of fixed places in the surrounding habitat will remain basically the same, other things being equal. This means that a system changing in the direction of increased sedentism should generate ancillary sites with increasing content homogeneity. This should have the cumulative effect of yielding a regional archaeological record characterized by greater intersite diversity among ancillary or non-residentially used sites but less intrasite diversity arising in the context of multiple occupations (Binford 1982:20).

From the more mundane perspective of the field archaeologist, Binford is pointing out that we have much to learn from small artifact accumulations generated during short duration use or occupation of a place. The durable material remains recovered from demonstrably short-duration sites are referred to as assemblages. One such assemblage, recovered from the West Tennessee Coastal Plain, is described here, and situated within our developing picture of the larger regional occupation of the land along the Hatchie River around AD 1200.

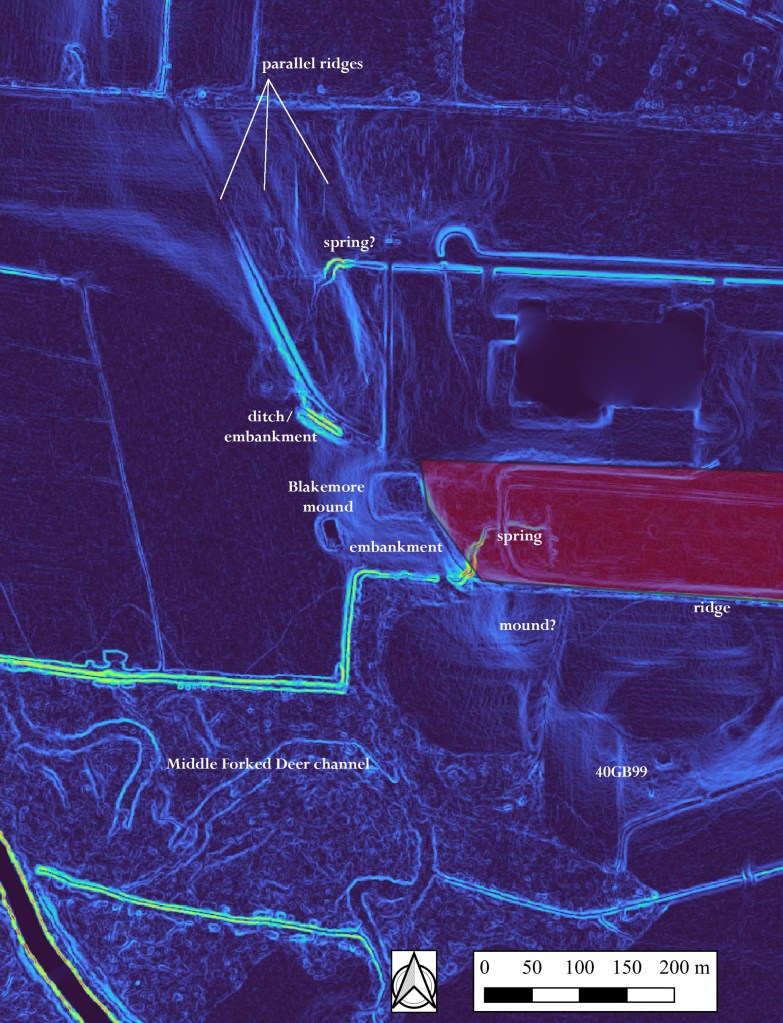

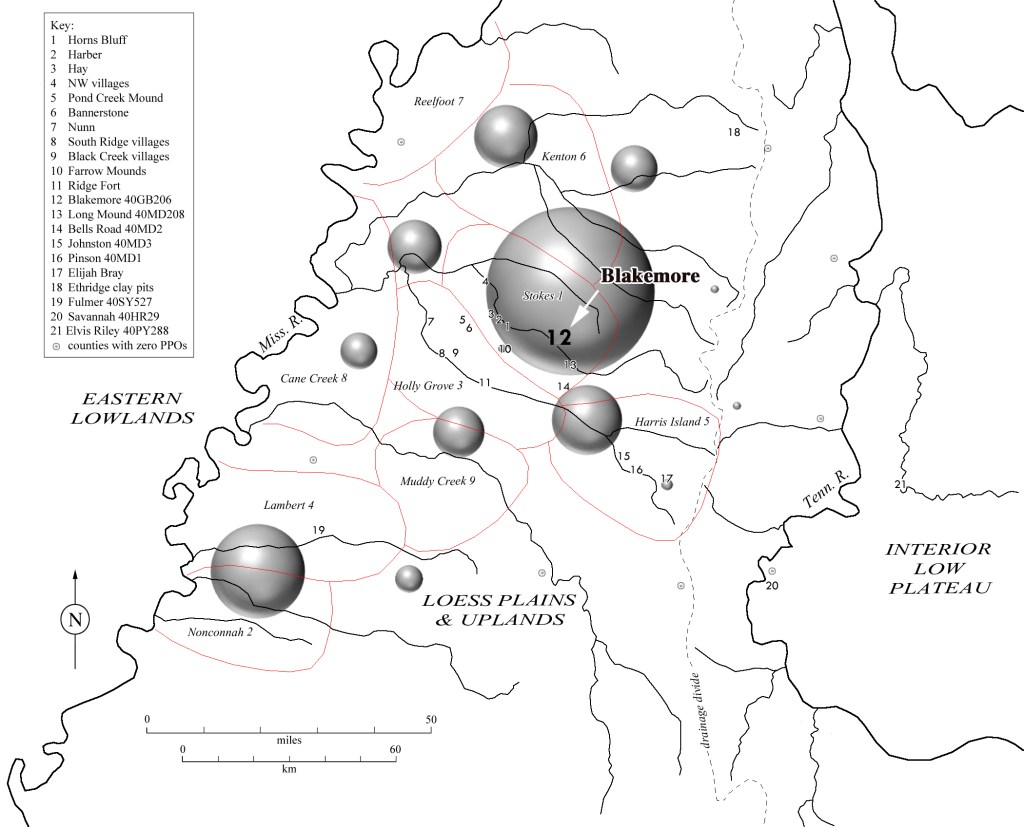

The Dry Branch site (40HM159) is situated on a long, elevated finger ridge of eroded silty clay loam between 460-465 feet above mean sea level (Figure 1). It is near the northern terminus of a substantial interfluvial upland separating Spring Creek and the main channel of the Hatchie River. An ancient major north-south Indian trail passed along this landform, crossing the Hatchie near present-day Bolivar, and continued to the northeast into the upper section of the Forked Deer and beyond (Figure 4; Ball 2014; Myer 1928). Another major trail ran from here to the Mississippi River west of the site. The nearest water is 220 m south-southeast, but the site is near the head of a small stream and permanent water may have been located at a greater distance from the site during early fall when precipitation is minimal. The site locale provides an excellent view of the lower lying narrow floodplain to the east.

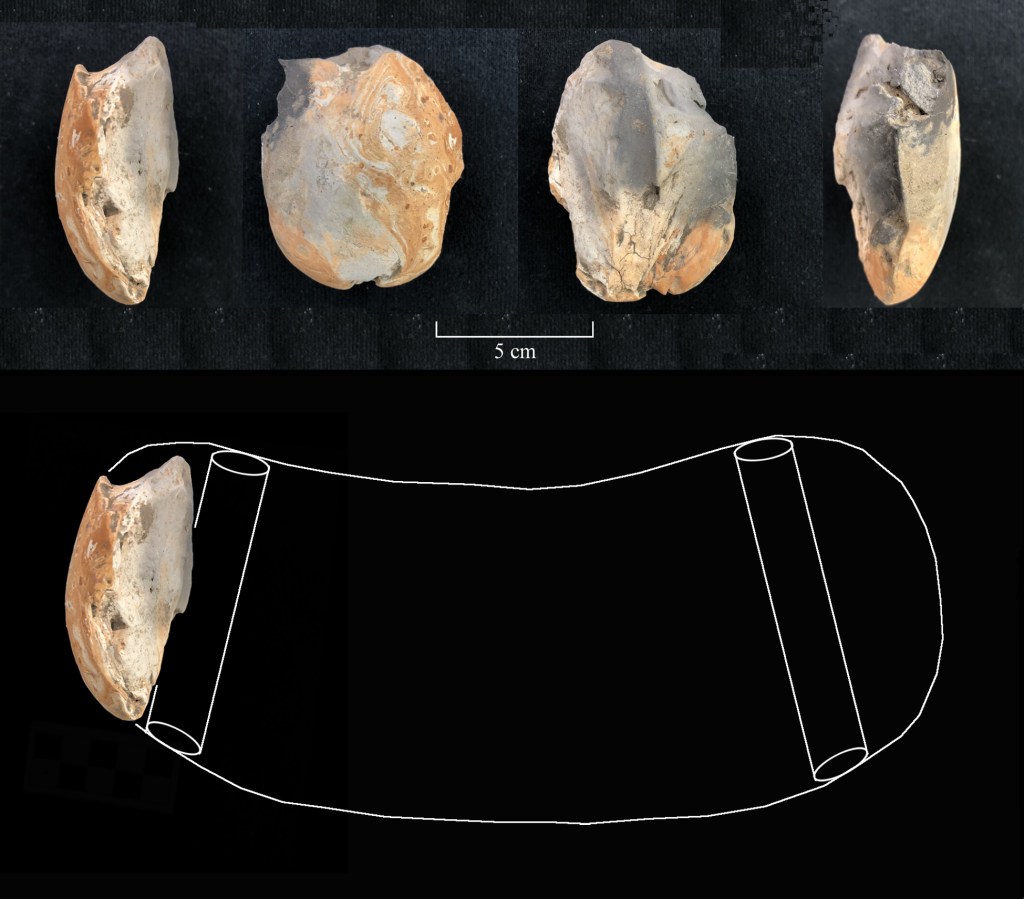

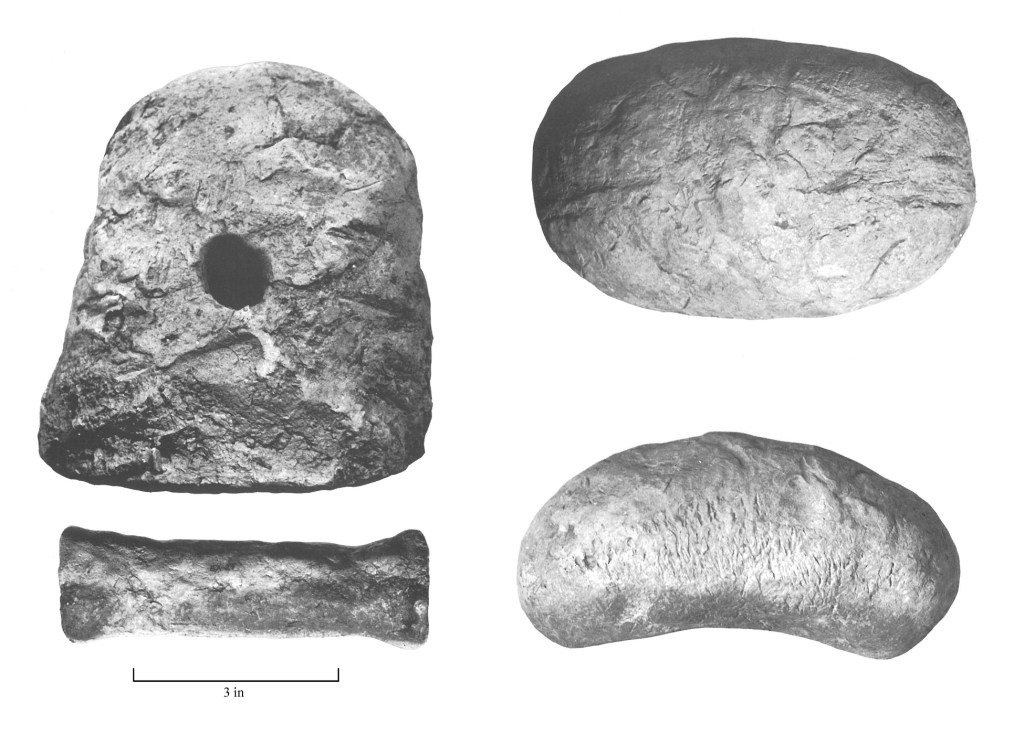

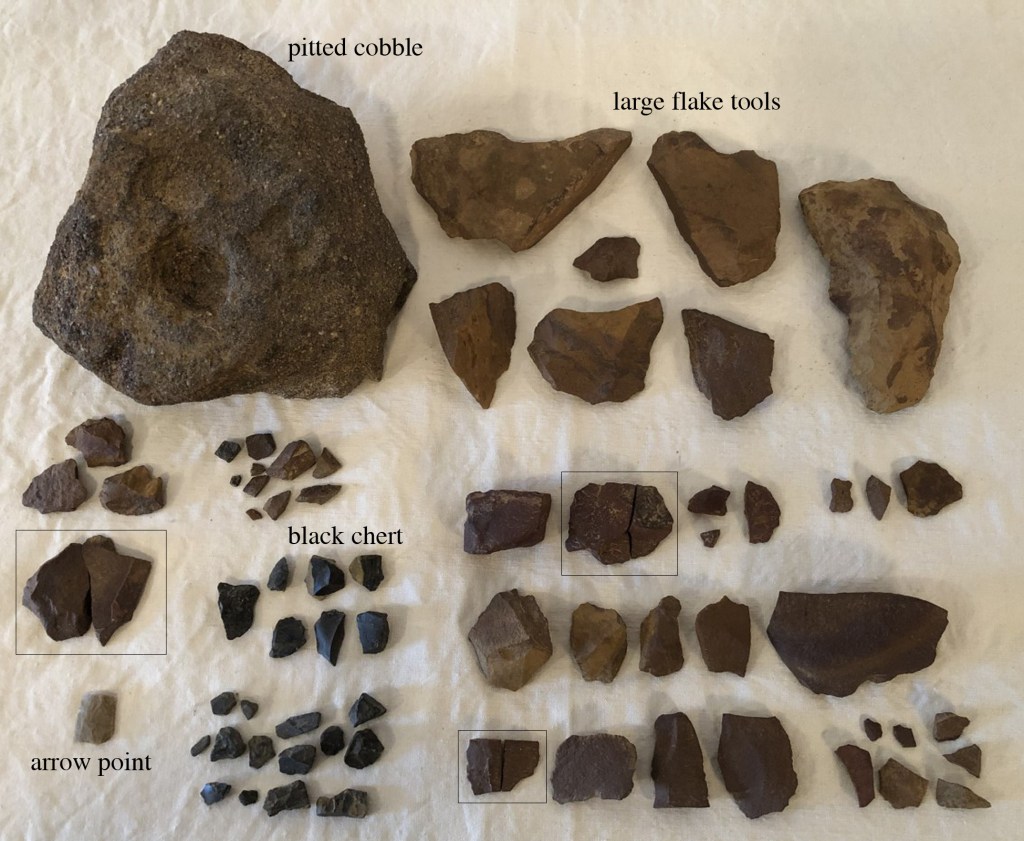

The Dry Branch site was initially identified in the fall of 2010 while walking fields adjacent to the parcel to the immediate north. Prehistoric artifacts were observed on the surface and periphery of an exposed field road in the vicinity of a stunted Catawba tree in an area covering no more than about 600 square meters. The farm road passing along the ridge post-dates 1950. This landform was wooded on the 1950 USGS quadrangle sheet and the subsequent photo-revision shows clearing of the ridge by 1983. The artifacts are restricted to the site surface and there is no indication of organic deposits. The surface material (Figure 2) has been rather systematically obtained after multiple visits to the ridge top over the past eleven years. During the initial inspection of the area the large unifacial ferruginous siltstone scraper (U) was found in a tilled patch of okra downslope and south of the main scatter. All other artifacts were within the boundaries shown on the aerial photograph. My last visit to the site area was during the late summer of 2021. At that time the place had been allowed to revert to wild vegetation and the site area was covered in a small stand of cane.

The medial portion of a small, finely chipped Hamilton or elongate Madison arrow point (two conjoinable fragments) of tan/gray chert is Mississippian in age. Dating of nearby sites (Pleasant Run 40HM2, Ames 40FY7, Denmark 40MD85) indicates a temporal range of ca. AD 1100-1300 (Hadley 2013, Mainfort 1992; Mickelson 2020). Other formal tools from the site include a large coarse-grained ferruginous sandstone (FeSS) mortar or “nutting stone” with a deep pit, two large well-made FeSS spokeshaves, a small steep-edged FeSS end scraper, a large unifacial FeSS scraper made on a primary decortication flake; a single utilized flake fragment was also recovered. Nearly all the debitage is locally available, fine-grained ferruginous siltstone (found at the base of the Claiborne formation, Figure 3; Thomas 1997). The limited number of parent blocks, high proportion of cortex on dorsal surfaces, and high percentage of conjoinable fragments in the small assemblage indicate a very short-term, limited activity site. No aboriginal pottery has been recovered from the site surface. Other than the chert arrow point, all the chert debitage from the site appears to be from a single, small black pebble. The activities of a single family, which included primary subsistence tasks such as processing hickory nuts, preparing deer skins, spotting game, and crafting and maintaining hunting equipment, are reflected in the durable material remains.

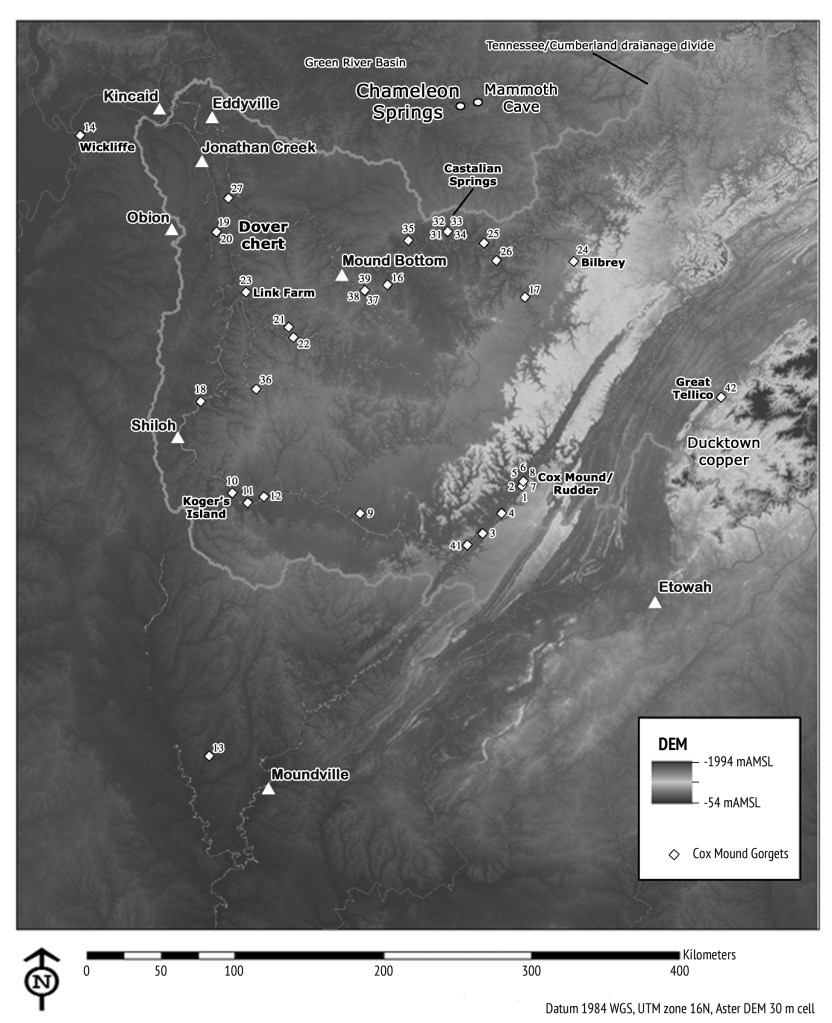

Dry Branch is within the day-trip radius of Pleasant Run, a ca. 13th century mound complex on the southwest side of the Hatchie River (orange circle in Figure 4). Approximately forty-five other archaeological sites of variable size and density have been identified in the same area, and many of them reflect the same kinds of ancillary activities and “content homogeneity” we should expect under conditions of reduced mobility and investment in a large and complex village and mound complex. Specifically, the sites reflect the same parochial use of locally available ferruginous stone, and the sites exhibit a consistent high ratio of this material to the more fine-grained silicious chert. Analysis of these archaeological places with the same level of detail that has been employed at Dry Branch would doubtlessly reveal some interesting intersite variability in the specific 13th century activities that were undertaken on the outskirts of the Pleasant Run village and mound complex.

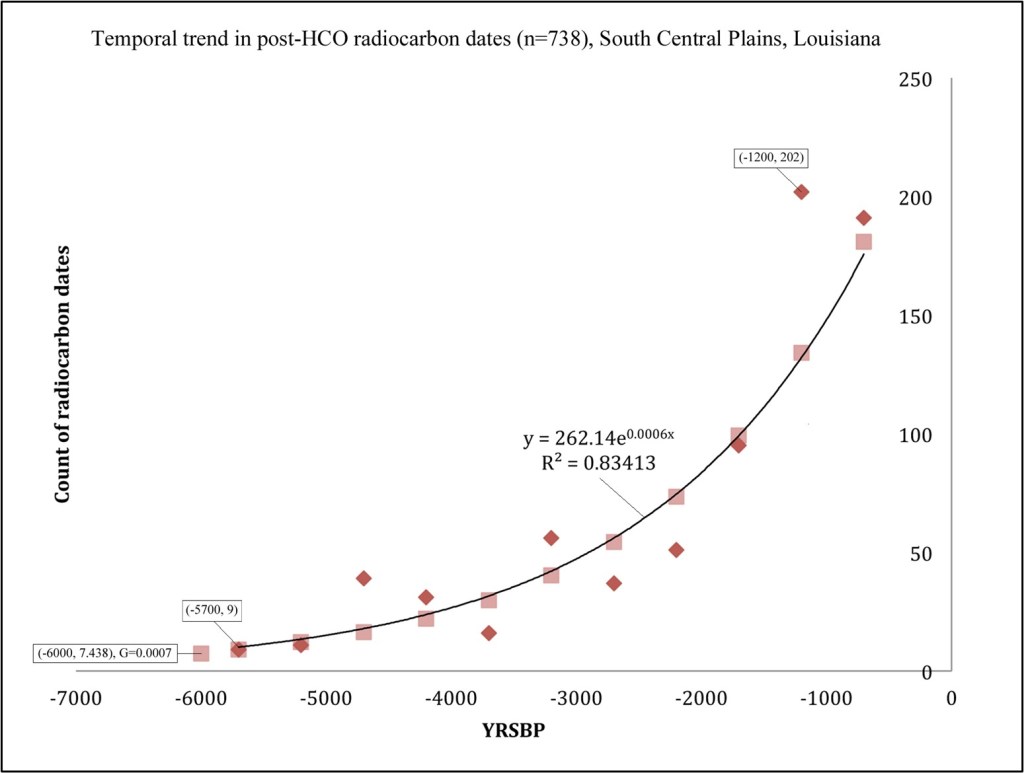

As noted in the discussion of the archaeological record in the larger West Tennessee region (see post on “Blakemore” September 2, 2022; Childress 2021: Childress et al. 1999; Smith 1979), the Hatchie River manifests as a temporally deep geophysical boundary marker. It is likely that small discrete “family places” like Dry Branch were part of a larger network of sites with affiliations to the west and southwest that extended to the margins of the loess bluffs bordering the Mississippi River alluvial belt and the upper Yazoo Basin. Research thus far indicates that the occupation of the region in the 12th and 13th centuries marked the terminus of intensive settlement and earthwork construction. After this time more concentrated site clusters are recorded closer to the larger channels of the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers.

This is where they walked, swam

Hunted, danced and sang

Take a picture here

Take a souvenir

— REM (Cuyahoga)

Acknowledgements: Satin Platt of the Tennessee Division of Archaeology in Nashville assisted in researching the assemblage characteristics of other sites in the vicinity of Dry Branch. James Elliott providing lodging and a stimulating environment during my numerous trips to the site area.

References Cited

Ball, D.B. (editor and compiler). 2014. William Edward Myer’s Stone Age Man in the Middle South and Other Writings. Borgo Publishing, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Binford, L.R. 1980. Willow Smoke and Dog’s Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation. American Antiquity 45:4–20.

Binford, L.R. 1982. The Archaeology of Place. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1:5–31.

Binford, L.R. 1983. Long Term Land Use Patterns: Some Implications for Archaeology. In Lulu Linear Punctated: Essays in Honor of George Irving Quimby, edited by R.C. Dunnell and D.K. Grayson, pp. 27–53. Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 72. Ann Arbor.

Childress, M.R. 2021. Blakemore Mounds (40GB206) and the Late Archaic–Middle Woodland Archaeological Record of West Tennessee. https://alabama.academia.edu/MitchellChildress

Childress, M.R., G.G. Weaver, and M.E. Starr. 1999. Discussion. In Archaeological Investigations at Three Sites near Arlington, State Route 385, Shelby County, Tennessee, compiled by G.G. Weaver, pp. 140-179. Tennessee Department of Transportation Environmental Planning Office Publications in Archaeology No. 4. Nashville.

Hadley, S.P. 2013. Multi-Staged Research at the Denmark Site, A Small Early-Middle Mississippian Town. Master’s thesis, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Memphis.

Mainfort, R.C., Jr. 1992. The Mississippian Period in the Western Interior. In The Obion Site: A Mississippian Center in Western Tennessee, by E.B. Garland, pp. 203-208. Report of Investigations 7. Cobb Institute of Archaeology, Mississippi State University, Starkville.

Mickelson, A.M. 2020. The Mississippian Period in Western Tennessee. In Cahokia in Context: Hegemony and Diaspora, edited by C.H. McNutt and R.M. Parish, pp. 243–275. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Myer, W.E. 1928. Indian Trails of the Southeast. In Forty-Second Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1924–1925, pp. 727–857. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington.

Smith, G.P. 1979. Archaeological Surveys in the Obion-Forked Deer and Reelfoot-Indian Creek Drainages: 1966 through early 1975. Memphis State University, Anthropological Research Center, Occasional Papers No. 9.

Thomas, D.W. 1997. Soil Survey of Hardeman County, Tennessee. USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service in cooperation with the Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station.